|

GUÉNOLA CAPRON Universidad Autónoma JÉrÔme

MONNET Université

Gustave Eiffel RUTH

PÉREZ LÓPEZ Universidad

Autónoma Recibido translation Jérôme Monnet

|

The sidewalk:

between traffic and other uses, the challenges of a hybrid urban order Abstract: Through a case study of the sidewalk in the Mexico

City metropolitan area, we use the notion of hybrid order to understand the

variable place that mobility and public space occupy in the ongoing logics of

the material, social and cultural production of different sidewalks. This

proposal contributes to a critique of European-centric conceptions of public

spaces and underlying dichotomies. The production and governance of sidewalks

are inscribed within a culture of informality common in Latin American, but

the concept of hybrid order can be extended to other objects and other

contexts. We conclude that the interest in walking and the sidewalk can lead

to a disruption of the conventional hierarchy that places at the bottom end

of governance the management of uses, by integrating it upstream in the

decision-making, planning and design processes. Keywords: Urban space; urban traffic; urban planning; Mexico.

La banqueta (acera): entre circulación y otros

usos, los retos de un orden urbano híbrido[1] Resumen: A partir del caso de estudio de las aceras en la zona metropolitana de la

Ciudad de México, utilizamos la noción de orden híbrido para entender el

lugar variable que ocupan la movilidad y el espacio público en las lógicas

que operan en la producción social y material de las diferentes banquetas.

Esta propuesta contribuye a una crítica de las concepciones eurocéntricas de

los espacios públicos. La producción y gobernanza de las banquetas se

inscriben dentro de una cultura de la informalidad común en ciudades

latinoamericanas, pero el concepto de orden híbrido puede extenderse a otros

objetos y contextos. Concluimos que el interés de caminar y por la banqueta

puede conducir a una ruptura de la jerarquía convencional que sitúa en el

extremo inferior de la gobernanza la gestión de los usos, al integrarla en el

extremo superior de los procesos de decisión, planificación y diseño. Palabras clave: Espacio urbano; circulación urbana; planificación urbana; México.

Cómo citar Capron, G.; Monnet, J. & Pérez, R. (2023). The sidewalk: between traffic and other uses, the challenges of a hybrid urban order. Culturales, 11, e763. https://doi.org/10.22234/recu.20231101.e763 |

Introduction

The original European conception of sidewalks makes them a part of the

public domain characterized by public uses, which is a matter of public order

and whose development and management belong to the public authorities (Gehl,

2010). Within this monopoly, the sidewalk may appear to transport and mobility

specialists as an element of the infrastructure for pedestrian circulation and

as a support for urban furniture that serves this circulation as well as that

of vehicles on the roadway. However, this functionality often seems to be

limited or even disrupted by many other uses, especially in cities of the

Global South, where the formal order of transit, which dominates the design of

streets, competes in particular with the alternative or even informal practices

of staying in public space to work, shop, consume, play or rest.

We are moving

away from the literature on sidewalks that puts the highlight on defaults of

accessibility, on walkability and urban design (Boils, 2019, 2022; Ingram et

al., 2017; Guío, 2008) and pedestrian mobility (Fernández-Garza &

Hernández-Vega, 2019; Tanikawa & Paz, 2022) and are following

Loukaitou-Sideris & Ehrenfeucht’s (2009) and Kim’s (2015) works on

conflicts, although with some differences. This situation of heterogeneity of

the uses of sidewalks has been studied in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam by Kim

(2015), who recommends managing the conflicts arising from it by going beyond

property rights focused on the public/private dichotomy and considering other

types of basic rights, particularly the right to subsistence. Extending Kim’s

proposal, we suggest here that the sidewalk has to be seen as the product of a

negotiated order in which informality plays an important role and that allows

for the coexistence of a variety of often conflicting uses, while at the same

time creating an ambivalent place for traffic.

Understanding the

production of the negotiated order of the sidewalk

means going beyond the dichotomy between public and private space. For this

reason, we do not adopt Kim’s notion of “mixed-use public space”, which implies

that the sidewalk is administered by public authority. Instead, we follow the

hypothesis that it is not only the physical space but also the order that

regulates the sidewalk that is hybrid, as it integrates and articulates

multiple dichotomies: public vs. private, formal vs. informal, residence vs.

work, and especially mobility vs. immobility. The notion of hybrid order that

we develop here for the study and interpretation of the sidewalk has

theoretical and methodological implications that could be extended to other

socio-spatial objects, whether related to mobility or not.

The perspective opened by the notion of hybrid order

allows us to analyze how pedestrian mobility practices that use the sidewalk as

a travel infrastructure, are inserted into the production of this order in

interaction with the other uses of the sidewalk. Our proposal is part of an evolution in urban planning

that integrates the plurality of uses by replacing the vocabulary and culture

of the roadway with those of the public space. What kind of order then

emerges from the hybridization at work?

We have chosen the concept of hybridization, following

García (1997) in his analysis of the evolution of contemporary cultures, where

he wants to mark a double distance: on the one hand, from the concept of

miscegenation (“mestizaje”), associated with the question of the mixing of

races, and on the other, from that of syncretism, used to evoke the fusion of

religious influences. However, the notion of “métissage” has been extended in

France to dimensions other than biological and has been used in Latin America

to conceive the “mestizo thought” (Gruzinski, 1999). Baby-Collin (2000) has

spoken of “mestizo urbanity” to show how the inhabitants of the precarious

neighborhoods of El Alto (Bolivia) and Caracas (Venezuela) produce their

urbanity and citizenship in a back-and-forth between formality and informality,

center and periphery, integration and exclusion. Recently, Runnels (2019) has

studied the “mestizo aesthetic” expressed in real estate development and

speculation in El Alto by entrepreneurs of Aymara origin.

It is in this sense of “mestizaje” that we place our

choice of the notion of hybridization to qualify the realities we have studied

through the sidewalks of the Mexico City area. We follow García (op. cit.)

when he draws attention to hybridization as an ongoing process rather than a

fixed state. Understanding this process means looking at developments on

different time scales and establishing the genealogy of the material and social

production of sidewalks as typical of successive or different generations of

urban planning and design. For example, the first “European-style” sidewalks

were imported to Mexico City by Viceroy Revillagigedo between 1789 and 1794,

marking a turning point in the imposition of public authority over residents

(Sánchez de Tagle, 2007). This process of public legitimation is consistent

with what has been observed elsewhere (Loukaitou-Sideris & Ehrenfeucht,

2007).

Another well-documented example of hybridization is

provided by the sidewalks of popular self-built neighborhoods. The origin of

these sidewalks is neither planning nor engineering, but vernacular know-how.

In some cases, the order of spatial separation between the sidewalk and the

roadway is created by farmers who have informally subdivided their land in

order to sell it, while the residents’ associations then create the physical

sidewalk with the means at hand and according to their own logic of use. In

other cases, the land has been occupied by force and the invaders carry out a basic

distribution of plots, on which the layout of the streets and (possibly) the

location of the sidewalks will be made later. For these different reasons, due to culture of informality

common in Mexico City and its surroundings, but also in other mexican and latin

american cities, the sidewalk appears as a hybrid property, because if

the residents recognize that it is public, at the same time they also feel that

it belongs to them, which explains why they can ensure the daily cleaning in

front of their house as we will see later. All this shows us the illusion of

making the street a “public space par excellence”, especially if it implies

that this space is undifferentiated, homogeneous, and monopolized by the State.

The focus on sidewalks, in a genealogical perspective

of the production of urban space, and thus attentive to the different

historical forms of production of urban space in different contexts, allows us

to highlight the intrinsic heterogeneity of the different places that make up

public space. In the street network, formally dominated by the order of

traffic, where public rules are nevertheless hybridized with social norms,

sidewalks appear as spaces of overlapping public and private logics, where

different normative regimes are superimposed, often incoherent with each other. The concept of a hybrid

order proves useful in explaining this social and cultural complexity of

regulations, practices, and perceptions that fundamentally impact mobility.

This proposal is the result of empirical research developed

in 2017-2022 in the metropolitan area of Mexico City and based on systematic

observations, interviews with governmental, associative, or economic actors,

questionnaires with users, video recordings and mapping of sidewalks at

different scales. Our objective was to consider the different modes of social

and spatial production of this fundamental urban space, as well as the

complexity of the phenomenology associated with it, and the relationships with

the different “settlement types” (Connolly, 2005) and “urban orders” (Duhau

& Giglia, 2008) existing in the metropolitan area.

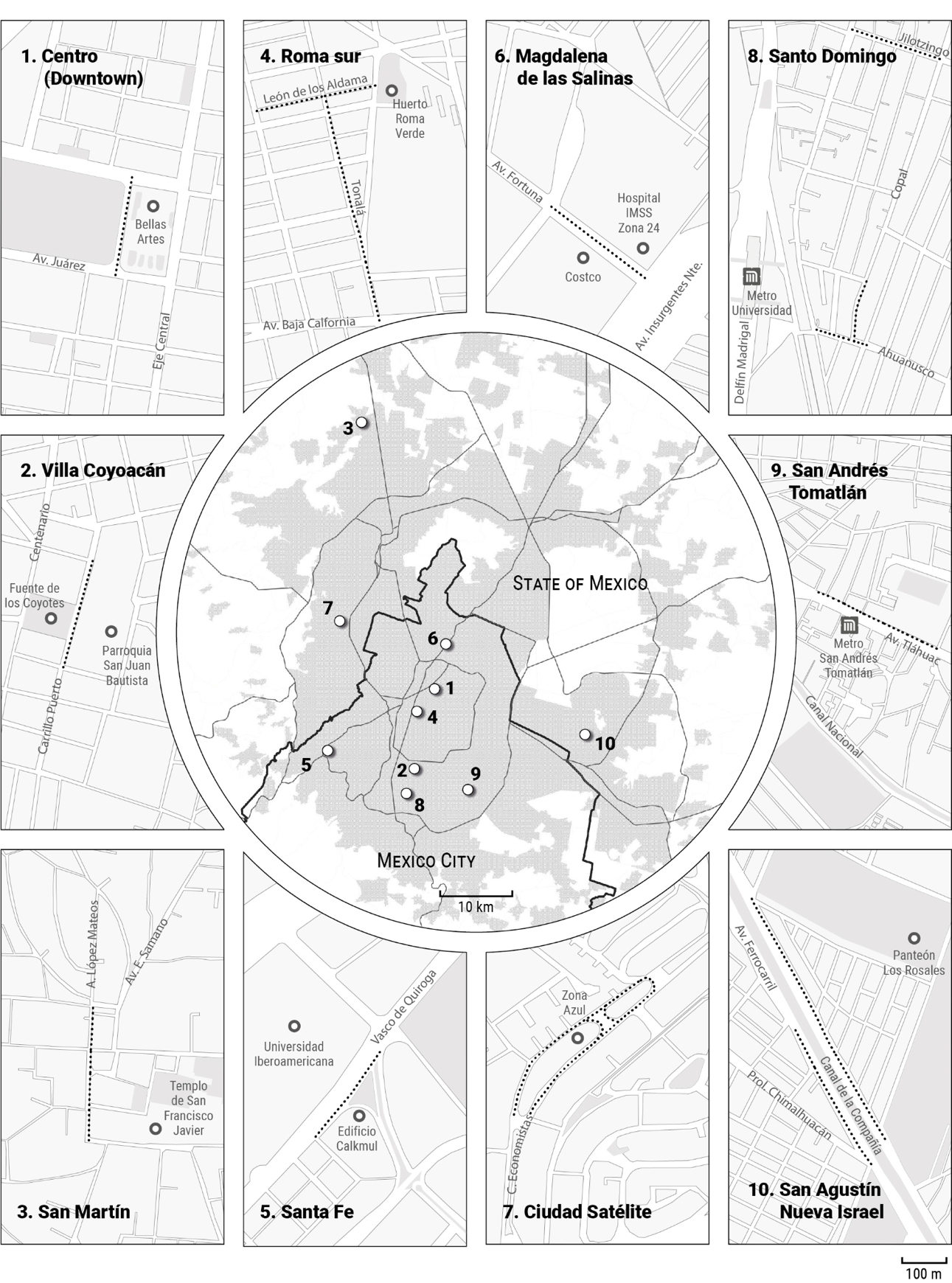

For this purpose, we selected a series of test sites

that corresponded to some of these types:

– two sidewalks in traditional central areas, one

located in the downtown historical district (Alameda central), the other in a

secondary historic and touristic area (Coyoacán), corresponding to the “city of

contested space” order in Duhau and Giglia’s typology;

– a sidewalk of the “island city” type corresponding

to a recent residential and business development linked to financial capitalism

(Santa Fe);

– three sidewalks in the popular residential areas of

the “city of negotiated space”, one corresponding to a “consolidated”

self-constructed neighborhood (Santo Domingo), another in a precarious area in

the process of urbanization (Nezahualcóyotl-Chimalhuacán border), and the last

one in a space in transition, where the sidewalks have been rebuilt by the

developers of two new shopping centers (Gustavo Madero);

– two sidewalks in the “ancestral city” on the

periphery of the metropolitan area, one in an old village incorporated into the

urban space (Iztapalapa) and the other in the center of a suburban town labeled

“magic village[2]“ (Tepozotlán);

– a sidewalk in the “homogeneous city”, in a

commercial area of a suburban development for the middle and upper middle

classes planned in the 1960s and 1970s (Ciudad Satélite).

Figure 1: Location of neighborhoods studied, Mexico City agglomeration.

Created

by: Jerónimo Díaz.

This paper is structured into five sections. Firstly,

we present a typology of sidewalks as a hybrid order, highlighting the specific

role of mobility in each type. Secondly, we describe the manifestations of the

hybrid order in material space. Thirdly, we analyze the socio-political effects

of hybridization. Fourthly, we examine how the hybrid order renews the strategy

for analyzing public space. Lastly, we explore comparative uses of the concept

of hybrid order.

The sidewalk as a

hybrid order: an attempt at typology

Our theoretical proposals and empirical results lead us to suggest the

following typology of practical modes of operation based on the hybrid order

concept, which encompasses mobility and other uses.

Sidewalks where the

legal order applied in a discretionary and non-linear way produces

contradictions and mixtures

In our study, this type of situation is exemplified by the sidewalk

running along the Alameda Park, in the historic center of Mexico City. This park

was created by the colonial authorities at the end of the 16th century. It

continues to be popular among both residents and tourists, who frequent it the

whole week and particularly on weekends. The sidewalk we studied is located at

the interface between this park and a vehicular access road to the underground

parking lot located under the square of the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of

Fine Arts, Mexico City Opera), itself an emblematic monument. The sidewalk

serving the pedestrian street (Madero) that leads to the Zócalo (Main Square)

of Mexico City, therefore, occupies a central place in pedestrian mobility

between the landmarks of the historic center, while hosting street performances

and many other uses. Formally, it is integrated into the management of the

park, where the prevailing regulation is precise and very restrictive in the

activities allowed, prohibiting a wide range of uses such as roller skating,

walking dogs, or vending. In practice, a whole range of omissions, tolerances,

compromises, and agreements emerge between enforcement officials and park

users. Three situations may illustrate the hybrid order in place:

a) formal rules that are not applied (by omission:

this is the case of children’s games in the fountains which were intended to

beautify the space, but became a playground for fun and refreshment, especially

during the hot season);

b) formal rules that are applied arbitrarily or on a

discretionary basis (users break the rule because they are not sure that it

will be applied; this is the case of skateboarders who, despite bans, continue

to practice until they are chased by the police);

c) informal rules (unrelated to the regulation) are

enforced (e. g., the police prohibit homeless people from sleeping on

benches, implying that benches can only be used for sitting, while the

regulation is not clear on this point, referring only to “the proper use of the

furniture”, cf. Giglia, 2016).

The enforcement of formal rules seems so uncertain

that police officers sometimes appear among the spectators of (in principle

prohibited) street performances. The discretionary nature of the application of

both formal and informal rules corresponds to a political logic in which hidden

agreements can be broken at any time.

Sidewalks where two formal

orders coexist and are in contradiction

Laws themselves can create uncertainty by appearing “fuzzy” or “muddy”

(“mud laws”, cf. Kettles, 2014). An example of this uncertainty is the

management of parking along sidewalks. Roadway space is nominally under public

management, even in self-built neighborhoods where residents have often built

the sidewalk in front of their homes. However, residents cite the lack of

parking and, more importantly, the risk of having parts of their car or vehicle stolen, to occupy

the pavement space in front of their homes. They place cans or other objects to

reserve this space for themselves and prevent other cars from parking there,

which can also be seen in other cities like Bucharest as a sign of privatism

(Popescu, 2022); this privatization of the curb is congruent with their control

and attention to the corresponding sidewalk, where they often decide on

legitimate uses. Residents and drivers generally respect this regulation, which

is not legal, but is consistent with the formal responsibility of residents to

clean the sidewalk in front of their homes and take care of the vegetation on

it (Law on Waste, Residuos Sólidos,

art. 39).

Thus, there is an unspoken hybrid

rule that says: “This is my parking lot between these points, and beyond that,

others can park”. However, the municipal authorities sometimes carry out

operations to remove the cans used to privatize the parking space, but the

residents immediately replace them; more often, these authorities tolerate this

use.

Generally speaking, the issue of parking blurs the

formal order of division between the sidewalk as pedestrian space and the

roadway as vehicle space. It is common for residents to park their vehicles

across the sidewalk in the driveway to their garage, leaving pedestrians only a

small passageway in front of the house or forcing them to walk on the roadway

turning around the vehicle. This situation, which is also common in front of

stores or other businesses to accommodate their customers’ vehicles, is also tolerated

by the police. In a metropolitan area like Los Angeles, this social practice

also gives rise to a hybrid order (Shoup, 2014).

In all these cases, a hybridization of multiple

figures of legality emerges, leaving open the question of who decides between

conflicting formal rules and offering the possibility of political play,

negotiation, while introducing uncertainty.

Sidewalks in a legal

vacuum:

in the absence of a formal order, a

hybridization regulated by informality

This case is represented by the road that forms the municipal border

between Nezahualcóyotl and Chimalhuacán, where each municipality claims

jurisdiction, but neither exercises it. There is no maintenance, no investment

by the government. The sidewalks here are built by the residents and are

sometimes materially very precarious or in poor condition, or simply do not

exist. The order of the motorized traffic is hardly present because very few

vehicles pass there, which allows the pedestrians to walk preferably on the

roadway. The division between the latter and the sidewalk is discontinuous and

not a matter of formal order. This situation is reproduced in many suburbs: if

frequent in popular self-built areas, it appears also in middle-class housing

estates, where the sidewalks built by the developers have never been taken care

of by the municipal authorities, who do not consider it as a priority.

Manifestations

of the hybrid order in space

We will use photographs taken during the research project to illustrate

these manifestations identified during the in-situ observations.

At the micro-scale of the ground, we observe material

hybridizations. For example, in Santa Fe there is a play of continuities and

discontinuities in the surface texture of the sidewalks. Photo 1 shows the texture

of the sidewalk built by the company that built a tower (left) and the texture

of the sidewalk built by the Delegation, the municipal authority (right).

However, photos 2 (sidewalk of the Delegation) and 3 (sidewalk built by the

company) show that on the one hand the “private” sidewalk reproduces the design

of the public sidewalk, but on the other hand the first one uses materials of

better quality than the second one.

Photo 1. Private sidewalk (left) and public sidewalk (right) in Santa Fe.

Credit: Ruth

Pérez López.

Photos 2 (top) and 3 (bottom). Textures and materials of the public sidewalk (photo

2) and the private sidewalk (photo 3).

Credit: Ruth

Pérez López.

Credit: Ruth Pérez López.

At the intermediate scale of the street, there is a

hybridization between the production of the material space (by private or

public actors) and the uses (public or private) that are made of it. For

example, in a residential street in the Roma Sur neighborhood, a resident has

built a bench that leans against the façade, in a style that matches that of

the house (photo 4). This bench is primarily intended for his use, to sit and

watch the animation of the street, but it is admitted that it also offers a

service to passers-by. This private device built by an individual thus imitates

the public bench device for both private and public use.

Photo 4. The resident’s bench, a service to passers-by.

Credit: Guénola

Capron.

Another situation is the support of street signs or

cables, trees or bus stops. They are often used to hang advertisements or

ropes, to install a kiosk, which often provides food services to people in

transit (Monnet et al., 2007). Another example is trees planted by

municipal authorities to provide shade and make walking or passing more

comfortable. Small and medium-sized trees are cut down by residents due to lack

of maintenance by the local government, which tolerates it. Photo 5 shows the

difference in treatment between trees maintained by residents and those

abandoned by the Delegation (Roma Sur).

Photo 5. Trees pruned by residents (background on the left) and trees abandoned

by the government (center).

Credit: Miguel

Ángel Aguilar.

The space

regulated by the hybrid order of sidewalk is thus the result of a negotiation

between public and private actors, which is part of the inhabitants’ and

government’s culture throughout the city. A very common

case is that of street vending, both in Mexico City and in Ho Chi Minh City

(Kim, 2015) and Nanjing (Guan, 2015). One of our previous research studies

showed the arrangements made between street vendors, establishments, and local

authorities, in particular to allow stalls to follow each other throughout the

day, creating a changing geography of the sidewalk (Monnet, Giglia, and Capron

2007).

The effects of

hybridization: mobility, safety, livability, democracy, integration-exclusion

The hybrid character of the order that reigns on the sidewalks and their

uses implies a series of consequences for the mobility, security, habitability,

integration and exclusion of the various actors that interact in these spaces.

Hybridization creates insecurity that threatens the

proletarians, but their leaders manage to become part of the political order

and allow the negotiation of tolerance for certain popular uses of space, in

particular the informal trade on the sidewalks, which lives on the pedestrian

traffic that provides it with its customers while often constituting an

obstacle to it. In fact, pedestrians who are in a hurry but who have nothing to

buy often have to walk on the roadway, at the risk of an accident.

The forms of appropriation of sidewalks that occur in

working-class neighborhoods are also found in other types of cities/urban

orders. Thus, in the “disputed city” which corresponds to the central city, as

in the case of the Roma neighborhood, the coexistence of residential, service,

and commercial uses generates numerous conflicts, for example over parking, as

we have seen above. Our findings confirm previous research showing that the

“negotiated” order is the dominant type in the agglomeration (see chapter “Los

usos de las reglas” in: Duhau & Giglia, 2008).

The constant negotiation of rules and the resulting

intrinsic uncertainty can be seen as the archetypal form of sidewalk governance

in Mexico City. In this context, everyone tries to take charge of the sidewalk

in their own way, either as a resident or as an occupier. In this context, the

formal order struggles to impose itself.

Nevertheless, there is a hierarchy between uses that

hybridizes “de jure” and “de facto” legitimations: while in law traffic imposes

itself on socialization, which in turn imposes itself on commerce, in fact this

hierarchy is sometimes exactly reversed. This could provide clues for the elaboration

of a “well-made” legal order. The hierarchy could then answer several

questions. Which order is more inclusive, the one that allows homeless people

to stay at the expense of pedestrian traffic, the one where a kiosk at a

crosswalk forces sidewalk users to walk on the road, or the one that excludes

all subsistence or convivial uses to impose traffic? When one actor imposes

itself on all the others, can the hybrid order be democratic and just? How the

most legitimate uses are defined and by who? In the case of the sidewalks of

Santa Fe and the Gustavo Madero Delegation, we observe the predominance of

privatization by real estate actors who try to make it the legitimate order,

limiting or repressing other uses that build on other legitimacies.

In Ho Chi Minh City, Kim (op. cit.) also raised

the question of the (de-)legitimization of the uses of the sidewalks and of the

street shops. She studied the opposing discourses on the latter where their

high social acceptability is evident, especially on the part of the residents,

the police officers in charge of the daily regulation of the sidewalks as well

as the civil servants who manage them. Examples of this kind can be found

elsewhere (Blomley, 2011; Valverde, 2012), including in an authoritarian

context such as China, where the hybrid order of sidewalks maintains the

appearance of a hegemony of the formal order (Guan, 2015). In Mexico City,

Ugalde (2016) showed the hybridization of different legitimacies in the

management of a tree planted in front of the door of a particular building,

whose growth prevented residents from getting their cars out of their garages

and which they wanted to cut down.

In this city, if there is strong discrimination

against street vending by the middle and upper classes, it is counterbalanced

by the tolerance of the working classes, who are the main beneficiaries of

these activities, both as workers and as customers. Thus, according to their

own moral values, as Guan (op. cit.) also observed in Nanjing, but also

because they belong to these social categories, public officials turn a blind

eye to these activities, depending on the place and/or time.

In the case of Latin American cultures, according to

García (1997), hybridization integrates more than it separates, especially in

the case of indigenous tactics in the face of the dominant colonial culture.

But hybridization creates a state of permanent uncertainty that makes the use

of space precarious, diminishing its intelligibility and the exercise of

certain rights, including the right to mobility. The democratic quality of the

hybrid order thus depends on the situations and orders. The hybrid order is

dynamic, because different uses prevail one after the other. Beyond the

observation of the heterogeneity of uses, hybridity shows the importance of the

interplay of actors interacting in the de facto and de jure management of

sidewalks.

Renewing the strategy

of analysis of public space

Critique of modern

Western public space

Urban public space has been the subject of much debate in the social

sciences over the last three decades. The crisis of public space has been

discussed with reference to its historical constitution in the large cities of

the Western world. An ideal public space is supposed to have emerged in

European and colonial cities in the modern era, before spreading around the

world with the industrial city. Its ideal characteristics include free access

for all, the primacy of individual circulation over immobility and static or

collective use of the street, and the anonymity of users. Since the middle of

the 20th century, this ideal corresponds to an urban project that claimed to

guarantee universal access to a set of goods and services for all inhabitants,

saw the emergence of a massive middle class, and offered conditions of full

employment to the working class in the context of the “Glorious Thirty”, known

in Mexico as the “Mexican Miracle” (Duhau & Giglia, 2008).

Public space is linked to the formation of a society

with unprecedented characteristics, and is the result not only of processes of

social inclusion, but also of new forms of regulation of urban life, which are

emerging in response to the problems created by industrialization, urban

expansion, the dispersion of working, living and shopping areas, and the

diversification of forms of housing and consumption. This raises the question

of urban order: At the origin of urban

public space, we find a question that remains central: the question of order, i. e. the forms of regulation of the uses of

the city. Public space, even if we like to think of it as an open and free space, is in fact marked in its essence not

only by the question of the coexistence of heterogeneous subjects, but in

particular by the question of common

rules, and of the common acceptance of rules, be they explicit or implicit,

formal or informal, rigid or flexible (Duhau & Giglia, 2008, p. 51;

emphasis in the original[3]).

We consider that insisting on urban hybrid order

-understood as the entanglement of rules of different purposes and origins-

allows us to go beyond the dichotomous vision typical of the modern Western

order, which separated public space from private space, pedestrian traffic from

automobile traffic (Monnet, 2010, 2016), and which prevailed in the planning of European cities,

and even more so in the planning of colonial cities where informal urbanization

was apart from formal urbanization. This statutory and physical

separation implied that public space became the domain of local public

authority.

In the current context of fragmented post-Fordist

cities, where privatized and segmented spaces proliferate, the public-private

dichotomy seems to be challenged by a wide range of actors. In France, the

“residentialization” movement closes and fragments the common open spaces of

large social housing complexes in the name of their safety. Around the world,

gated communities and other secure residential areas have been created, with

access and management under the responsibility of private co-owners (Capron et

al., 2018). Business Improvement Districts in many cities around the world

have transferred the supervision, maintenance, and animation of public spaces

to retail and business associations, while public-private partnerships have become

common in building construction and open space design. Conversely, private uses

of public spaces have been renewed and transformed by mobile information and

communication technologies or with the rise of the sharing or platform economy

(self-service vehicles, door-to-door food delivery, etc.). These changes have

made the regulation of the use of public space extremely complex, involving a

greater variety of public and private actors.

This complexity is linked to the emergence, in the

last twenty to thirty years of new trends in urban planning that promote the

requalification of public space to improve the quality of urban life, according

to a conception of conviviality that is often limited to attractiveness. Thus,

the place making movement illustrates a set of trends that promote

participation, tactical urbanism, and events, but mostly concern the

development of consumption and leisure in selected places (Friedman, 2010;

Peza, 2022). The analysis of these trends is not the purpose of this paper, but

we can point out that their use and effects are far from being homogeneous and

effective, and that they are subject to criticism, often in relation to their

consequences in terms of gentrification[4].

What we want to emphasize here, in relation to the issue

of sidewalks and mobility, is the importance of analyzing in detail the concrete uses of these basic

public spaces, in order to capture the social and cultural complexity of

the practices, normative regimes and social representations associated with these

places. In this way, serious research can contribute to the evaluation and

possible critique or improvement of proposals such as place making.

The sidewalk as a

hybrid order

Why talk about order instead of hybrid space? The concepts of third

space or third place, intermediate or hybrid space, have been used to qualify

co-working spaces, at the intersection between housing, office and

conviviality, but also for intermediate spaces between the rural and the urban

(Bonerandi et al., 2003). The co-working space “articulates the

flexibility of self-employment with the social environment of organizations,”

in a context characterized by a great diversity of interactional situations and

by the efforts of co-workers to produce cooperation, between the defined and

the undefined, between restriction and freedom (Trupia, 2016). Thus, the hybrid

co-working space appears ambiguous, neither public nor private. The ability of

the spatial device to produce or foster cooperation or innovation seems to

depend on the self-fulfilling prophecy that its hybridity does not make it a

workplace like any other.

The notion of Third Space is mobilized by Soja (1996)

to evoke a space between the concrete and the imaginary. As far as we are

concerned, hybridization goes beyond the observation of the heterogeneity and

complexity of the uses and material forms of the sidewalks, to allow us to

analyze the processes of production of orders, or in other words, of the

ordinations that link and hierarchize this heterogeneity and complexity.

We therefore privilege the notion of order (Duhau

& Giglia, 2008), rather than that of hybrid space, as the interpretive key

to the governance of sidewalks as spaces for pedestrian (and micro-vehicles)

circulation that coexist with other, more static uses. According to this

perspective, the sidewalk appears as a sui generis space resulting from a

hybrid order. This reflects changes in spatial organization based on the

distribution of actors, their interactions, behaviors, interests, and

appropriations, as well as the mobilization of different processes or formal

and informal norms. As such, it is a performative reality that is both

normative and practical, extending beyond and connecting the realms of formal

and informal, mobile and stationary, and public and private.

How is all this “put in order”? Much of what happens

between the legally and socially private space of the parcel on the one hand,

and the roadway put in order by and for traffic on the other, does not

correspond to what is theoretically expected of a public space. In this

interval, the order is pragmatic and does not depend on the spatial dichotomy

of public and private. The sidewalk appears neither as a pure public domain nor

as a simple extension of the private into the public, but as a spatialized

hybrid order, in which the power relations between different orders are

expressed. It thus embodies a specific governance that regulates a variety of

uses in which neither the order of traffic (hegemonic on the road) nor the order

of intimacy (essential in private space) dominates.

García (1997) suggests that hybridization, in the

context of conflicts between modernity and the traditional-modern dichotomies,

should not be seen as an imposition but rather a creative process that takes

place between desired modernity and tradition (especially indigenous) that we

do not want to lose. In Mexican cities, this is illustrated by the persistence

of tianguis (open-air markets) and

itinerant commerce, while “modern” forms of commerce have developed (department

stores, shopping malls, and now online commerce). In the same vein, both Michel

de Certeau (1990) and Gruzinski (1999) evoked the “tactics” of the dominated to

adopt the legalism of the dominant and subvert it by integrating it into their

different belief systems and customs, in a new register.

The tension between the durable and the ephemeral, the

formal and the informal, among others, gives great instability to the hybrid

order of sidewalk, for at any moment it can be challenged, revoked, or

complicated.

The significance of

the hybrid order for the comparison of urban spaces

The concept of hybrid order has a theoretical-methodological importance

because, beyond the need for an internal comparison of sidewalks in the metropolitan

area of Mexico City, it allows a comparative analysis of different spatial

management situations in different urban contexts, considering their

complexity, while avoiding the confinement in dichotomies such as

public-private, formal-informal, traffic-parking or residential-work, among

others.

To illustrate this point, let us consider the case of

cities where, in principle, the formal order seems to be more present and

better respected, such as in France or Canada. The concept of hybrid order seems

to contribute to a better understanding of the de jure and de facto management

of sidewalks.

In Paris, the local government usually assumes

responsibility for sweeping the streets from one facade to another. On the rare

occasions when snow accumulates, an exceptional formal order is implemented,

reserving the authority to clear the roadway for vehicles, while in principle

the residents are responsible for removing the snow from the sidewalks. Two

phenomena hybridize this formal rule: on the one hand, the technique used to

clear the roadway causes the municipal services to push the snow back onto the

sidewalks; on the other hand, the residents completely ignore their

responsibility to clear the sidewalks, following the habit of considering that

cleaning is the responsibility of the municipal services.

In Canada, snow is commonplace and municipal decrees

require residents to remove snow from sidewalks, a well-known and practiced

rule. The regulation dictates that residents must ensure the continuous passage

on sidewalks to avoid liability for any accidents caused to pedestrians.

However, this responsibility can shift to the municipality in the absence of a

decree or in streets where the authority uses machines adapted for snow removal

on the sidewalks.

The cases of Canada and Paris thus allow us to

hypothesize that, even in contexts in which all actors are convinced that the

formal order is hegemonic, with a transparent and predictable application,

there are circumstances in which a degree of hybridization of rules and

practices appears that an in-depth study could reveal.

Beyond the archetypal public space of the street, the

concept of hybrid order can also be applied to spaces whose “public” character

is not always obvious, such as the internal pedestrian circulation spaces of

large residential or office complexes of functionalist architecture. In what is

known in France as “urbanisme de dalle” (Picon-Lefebvre, 2001), the level of

pedestrian circulation “above the street” is the subject of many conflicts (between

users and between managers) and poses major challenges. Similarly, the feet of

social housing buildings, long used as public spaces when they were privately

owned, are subject to contradictory trends to resolve conflicts of use: the

strong trend is towards “residentialization” by fencing them off to make them

private spaces, but there is also the opposite trend of transferring ownership,

development and maintenance to the local government (Lelévrier & Guigou,

2005).

The range of hybrid orders is therefore very wide. In

Mexico City, we could also cite the case of parks opened to the public by the

local government on private land (example of Reforma Social Park) or of

shopping centers that are public-private spaces (Capron, 1998).

Conclusions

Each case deserves an in-depth study of the hybridization processes at

work locally, but the theoretical-methodological dimension of the concept of

hybrid order makes it possible to envisage robust comparisons by making visible

uses other than pedestrian transit on sidewalks.

In the Mexico City metropolitan area, the accumulation

of local micro-orders with varying degrees of hybridity makes the governance of

sidewalks extremely complex and unstable. This seems a far cry from the

situation in New York City studied by Jane Jacobs (1961, 1989) in the

1950s. In Mexico City, uncertainty

dominates, making the sidewalk a flexible space, the product of a permanent

negotiation between actors, in which users are a more active part than in other

contexts.

This is probably due to the socio-cultural

particularities of the urbanization process in Latin America. In this region,

during times of deep urbanization, there was few planning and development

regulations or they were not complied with (for example, lots were sold in places

that did not have infrastructure or services), so that inhabitants were forced

not only to build their own homes, but also to build facilities and

infrastructure and manage urban services (Pírez, 2013). Unlike other highly

regulated contexts, in the metropolitan area of Mexico City there is strong

citizen participation (formal and informal) in the design, construction and

modification/rehabilitation of sidewalks, as well as in their management.

According to us, this informal urbanization, and above all, the place that

informality occupies even in other urban contexts that are more formal,

contribute to explain the processes of hybridization in the production and

management of sidewalks. In other words, hybridization is closely linked to the

informality present in urban planning and development processes.

The hybrid order leads to unstable processes of

exclusion or inclusion, but also allows the city to continue to function. We

therefore echo Kim’s (2015) call for local governments to create “laboratories”

that bring together actors (passersby, merchants, residents, police, activists,

academics, etc.) to explore sidewalk governance that balances the need for

stable and consistent legal protection with the flexibility of local

functioning.

We have applied the concept of hybrid order to

sidewalks, and it would be interesting for future research to explore its

application to other objects, including real estate speculation, transportation

management, and waste administration. Examples of such applications can be

found in Boltvinik (2018) about garbage and they encompass the intersection of

formal urbanism, technocracy, and social accommodation. Even in contexts as the European ones, where

publicity and formality are higher, hybrid order can be a productive issue to

analyze blurred situations between public and private or formal and informal.

Acknowledgements

This paper builds upon

empirical results from case-studies completed by Miguel Ángel Aguilar, Guénola Capron, Silvia Carbone, Perla

Castañeda, Eliud Gálvez, Ana Luisa Diez, María Teresa Esquivel, Angela Giglia (†), Salomón González Arellano, Bismarck

Ledezma, Ruth Pérez, Natanael Reséndiz and

Alejandra Trejo Poo. A special acknowledgement to Angela Giglia who helped to

write the chapter “La banqueta, un orden híbrido” in the book “Banquetas: el

orden híbrido de las aceras en la Ciudad de México y su área metropolitana”

(UAM-Azcapotzalco).

Bibliographic

references

Baby-Collin, V.

(2000). Marginaux et citadins. Construire une urbanité métisse en

Amérique Latine. Etude comparée des barrios de Caracas (Vénézuela) et des

villas d’El Alto de La Paz (Bolivie)

[Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Université de Toulouse-2 le Mirail. https://www.theses.fr/2000TOU20066

Blomley, N. (2011). Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the regulation of

public flow. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Rights-of-Passage-Sidewalks-and-the-Regulation-of-Public-Flow/Blomley/p/book/9780415598378#

Boils, G. (2019).

Diseñar banquetas accesibles para todos. Academia

XII, 10(20), 23-38.

Boils, G. (2022).

Personas con discapacidad, banquetas e insensibilidad. In M. Camarena & V.

Moctezuma (Eds.), Ciudad de México,

miradas, experiencias y posibilidades (pp. 197-225). UNAM, IIS.

Bonerandi, E.; Landel, P. & Roux,

E. (2003). Les espaces intermédiaires, forme hybride : ville en campagne,

campagne en ville? Revue de géographie

alpine, 91(4), 65-77. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rga_0035-1121_2003_num_91_4_2263

Boltvinik, I.

(2018). Remover y esconder, acumular y

dispersar: Geografías de la basura en la Ciudad de México [Unpublished

doctoral dissertation]. UAM-Cuajimalpa. http://ilitia.cua.uam.mx:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/283

Capron, G. (1998).

Les centres commerciaux à Buenos Aires.

Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, 78, 55-64.

Capron, G.; Monnet, J. y Pérez, R.

(2018). Infraestructura peatonal: el papel de la banqueta

(acera). Ciudades, 119, 33-40.

Connolly, P.

(2005). Tipos de poblamiento en la Ciudad de México. UAM-Azcapotzalco.

De Certeau, M. (1990). L’invention du quotidien. 1. Arts de faire.

Gallimard.

Duhau, E. &

Giglia, A. (2008). Las reglas del

desorden. Habitar la metrópoli. Siglo XXI.

Fernández-Garza y Hernández-Vega (2019). Estudio de la

movilidad peatonal en un centro urbano. Un caso en Costa Rica. Revista Geográfica de América Central, 62, 244-277.

Friedmann, J.

(2010). Place and Place-Making in Cities. A Global Perspective. Planning Theory & Practice, 11(2), 149-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649351003759573

García, N. (1997).

Culturas híbridas y estrategias comunicacionales. Estudios sobre las Culturas Comunicacionales, 5, 109-128. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/316/31600507.pdf

Gehl, J.

(2010). Cities for people. Island

Press. https://islandpress.org/books/cities-people

Giglia, A. (2016).

Reglamentos y reglas de usos de la Alameda Central de la Ciudad de México: un

régimen híbrido. In A. Azuela (Ed.), La

ciudad y sus reglas. Sobre la huella del derecho en el orden urbano (pp.

381-422). UNAM/ PAOT. https://ru.iis.sociales.unam.mx/bitstream/IIS/5234/1/ciudad_y_sus_reglas.pdf

Gruzinski, S. (1999). La pensée métisse. Fayard. https://www.fayard.fr/histoire/la-pensee-metisse-9782213602974

Guan, L.

(2015). Le

commerce ambulant et son espace social à Nankin (Chine) : enjeux et

perspectives urbanistiques (Unpublished

doctoral dissertation). Université Paris-Est.

Guío, F. (2008). Recomendaciones de diseño para

infraestructura peatonal en Colombia. Revista

Facultad de Ingeniería, 17(25),

39-52.

Ingram, M.; Adkins, A.; Hansen, K.; Cascio, V. & E.

Somnez (2017). Sociocultural

perceptions on walkability in Mexican American neighborhoods: implications for

policy and practice. Journal of Transport & Health, 7(B), 172-180.

Jacobs, J.

(1961 [1989]). The Death and Life of

Great American Cities. Random House.

Kettles, G.

(2014). Crystals, Mud, and

Space: Street Vending Informality. In V. Mukhija & A.

Loukaitou-Sideris (Eds.), The Informal

American City. Beyond Taco Trucks and Day Labor (pp. 227-243). The MIT

Press.

Kim, A. (2015).

Sidewalk City. Remapping Public Space in

Ho Chi Minh City. The University of Chicago Press.

Lelévrier, C.

& Guigou, B. (2005). Les Incertitudes de la résidentialisation.

Transformation des espaces et régulation des usages. In B. Haumont & A.

Morel (Eds.), La Société des voisins

(pp. 51-68). Maison des Sciences de

l’Homme.

Loukaitou-Sideris,

A. & Ehrenfeucht, R. (2007). Constructing the sidewalks: municipal

government and the construction of public space in Los Angeles, California,

1880-1920. Journal of Historical

Geography, 33(1), 104-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2005.08.001

Loukaitou-Sideris,

A. & Ehrenfeucht, R. (2009). Sidewalks.

Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space. The MIT Press.

Monnet, J.; Giglia, A. & Capron, G.

(2007). Ambulantage et services à la mobilité : les carrefours commerciaux à

Mexico. Cybergeo: European Journal of

Geography. https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.5574

Monnet, J.

(2010). Dissociation et imbrication du formel et de l’informel: une matrice

coloniale américaine. Espaces &

Sociétés, 143, 13-29. https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.143.0013

Monnet, J.

(2016). Marche-loisir et marche-déplacement:

une dichotomie persistante, du romantisme au fonctionnalisme. Sciences de la Société, 97, 75-89. https://doi.org/10.4000/sds.4075

Peza, E.

(2022). City of fear: feelings of

insecurity, daily practices and public space in Monterrey, Mexico

(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Paris.

Picon-Lefebvre,

V. (2001). La dalle moyen de séparation des trajets à des vitesses variables. In

C. Prelorenzo & D. Rouillard (Eds.), Mobilité

et esthétique, deux dimensions des infrastructures territoriales (pp.

29-36). L’Harmattan.

Pírez, P. (2013).

Los servicios urbanos en América Latina. In B. Ramírez & E. Pradilla

(Eds.), Teorías sobre la ciudad en América Latina (pp. 455-504). UAM.

Popescu, R. (2022). The culture of parking on the

sidewalks. Cities, 131, art.133888.

Runnels, D.

(2019). Cholo aesthetics and mestizaje: architecture in El Alto,

Bolivia. Latin American and Caribbean

Ethnic Studies, 14(2), 138-150 https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2019.1630059

Sánchez de

Tagle, E. (2007). Los dueños de la

calle. Una historia de la vía pública en la época colonial. INAH.

Shoup, D.

(2014). Informal parking market: turning problems into solutions. In V. Mukhija

& A. Loukaitou-Sideris (Eds.), The

Informal American City. Beyond Taco Trucks and Day Labor. The MIT Press.

Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace. Blackwell.

Tanikawa, K. & Paz, D. (2022). El peatón como base de una movilidad urbana sostenible:

una visión para construir ciudades del futuro. Boletín

de Ciencias de la Tierra, 50,

33-38.

Trupia, D. (2016). Produire un espace

hybride de coopération. Une enquête ethnographique sur La Cantine. Réseaux, 2(196), 111-145. https://www.cairn.info/revue-reseaux-2016-2-page-111.htm

Ugalde, V. (2016). Del papel de la

banqueta: testimonio del funcionamiento de la regulación urbana ambiental. In

A. Azuela (Ed.), La ciudad y sus reglas.

Sobre la huella del derecho en el orden urbano (pp. 115-140). UNAM/ PAOT.

Valverde, M.

(2012). Everyday Law on the Street. City

Governance in an Age of Diversity. The University of Chicago Press.

Guénola Capron

Franco-mexicana. Doctora por la Universidad de Toulouse-2 le Mirail

(Francia), con especialidad en geografía y ordenamiento territorial. Es

maestra en Urbanismo y licenciada

en Geografía por la Universidad de París-1. Actualmente se desempeña como

profesora-investigadora en la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Azcapotzalco.

Líneas de

investigación: geografía y sociología urbana, estudio de la transformación del

espacio público en las ciudades latinoamericanas. Últimas

publicaciones: Coeditor en Banquetas: el orden híbrido de las aceras en la

Ciudad de México y su área metropolitana (2022) y coautor en “La banqueta insegura en una colonia en vía de

gentrificación: la construcción de los otros desde las relaciones vecinales”

(2022).

Jérôme Monnet

Francés.

Doctor en Geografía por la Université de

Paris-4 Sorbonne. Profesor de la Universidad Gustavec

Eiffel en Francia, codirector de la Escuela de Urbanismo de París e

investigador del Laboratorio Ciudad-Movilidad-Transporte. Especialista de los

espacios públicos en las grandes metrópolis (París, Ciudad de México, Los

Ángeles), sus estudios enfocan las políticas urbanas y los usos sociales, entre

otros la movilidad no motorizada, el comercio, la informalidad. Líneas de investigación: movilidad urbana,

caminar en la ciudad, espacio público, geografía urbana, urbanismo. Últimas publicaciones: Coeditor en Banquetas:

el orden híbrido de las aceras en la Ciudad de México y su área metropolitana (2022);

Coautor en “Trottoir: les multiples facettes d’un

espace public de loisirs. Le cas de Mexico” (2022).

Ruth Pérez

López

Mexicana-española. Doctora en

Cambio Social por la Universidad de Lille1 (Francia) y miembro del Sistema

Nacional de Investigadores de México (Nivel 1). Profesora-investigadora de la

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Azcapotzalco, coordinadora de Eje Docente de

Sociología Urbana y secretaria del Consejo Directivo de la Asociación

Bicitekas, A.C. Líneas de investigación: movilidad urbana cotidiana de la

población metropolitana, movilidad no motorizada (cruces peatonales y

banquetas), relaciones de poder entre peatones y conductores de vehículos

motorizados, procesos de apropiación de las banquetas, la coexistencia de usos

y la negociación de órdenes locales entre los actores que las producen y las

gestionan. También realizó estudios sobre la movilidad en bicicleta. Últimas publicaciones: Coautora en “‘Footbridges’: pedestrian infrastructure or

urban barrier?” (2022); Coeditora en Banquetas:

el orden híbrido de las aceras en la Ciudad de México y su área metropolitana.