The construction of female

citizenship is read as a paradox by Joan Scott when she points out that “the

history of feminism is the history of women who have only paradoxes to offer” (Scott, 2012, p. 21). Insofar as Western democracies constructed

citizenship based on the equivalence between individual and masculinity, Scott

points to the paradox involved in simultaneously defending the importance and

irrelevance of sexual difference when demanding rights such as voting or

education.

This key

paradox in the construction of equality and difference in modern times also

marked the gendered character of both national and civilizing projects, largely

articulated by the sexual division of labor and by a family-focused and

domestic iconography that differentiated roles, discourses, and practices in

sex-gender terms (McClintock, 1993). As Yuval Davis and Anthias

(1989) point out, although women

who participated as civilizers in the architecture of these projects often

faced the same or more risks as their male counterparts, they have been

represented from a pre-political conceptualization of affects, in a

relationship of love or support towards conquerors, soldiers, or missionaries.

Thus, once the war was over, the discourse of national sentimentalism calls

upon these civic mothers to build peace among all those who were previously

enemies, that is, to embody “the gentle hand of power” in order to construct a

society (Vera, 2016).

The first decades of the 20th century in Chile

correspond to a period of rhetoric of national unity that advocated for the

need to integrate social and ethnic sectors which had been explicitly excluded

since colonial times. This period also coincides with the significant unfolding

of female professionalism (midwives, social workers, nurses, teachers), which

Lavrín conceptualizes as “scientific motherhood”: women who were key for social

change as they would be in charge of “sanitizing and moralizing the sexual

sphere in order to build a healthy and strong nation” (Lavrin, 1995, p. 88;

Illanes, 2007; Vera, 2016). This period was also defined by alliances between

the Catholic Church and elite women’s philanthropy (Yeager, 2005), the feminization of education (Egaña et al., 2003), and, globally, the feminization of missions (Haggis, 1998; Semple, 2003; De la Fuente, 2023).

We propose paradoxical strategies as a key approach to interpreting the

discourses of a subject who is little or problematically integrated into the

reflection on female and eventually feminist genealogies in Chile: religious

women (Haggis, 1998; Vera & Valderrama-Cayumán, 2017). As Haggis

points out, such genealogies have generally tended to consider religiosity as

“an unfortunate conservative influence” in women’s history (Haggis, 1998, p. 173). In the case

of Chile, Yeager argues that religion was a key tool for integrating women into

modernization processes. Far from secular feminism, religious women who were in

charge of the education of girls and teachers since the late nineteenth century

fostered, however, a female self-awareness. This would have allowed to

politically intend the idea of female moral superiority in order to form

“guardians of national morality” (Yeager, 2005, p. 243). One of the subjects that

emerges from this reading, against the grain of women’s histories and

feminisms, are the missionaries.

Haggis´s work on British evangelical missionaries points out that within

the intertwined discursive framework of religion and empire, “rather than an

emancipatory struggle to break through the bounds of convention, it was

precisely convention which enabled the making of the female missionary (Haggis, 1998, p. 172). Through this “flexible and

subtle reordering of existing norms and values”, the author asserts that

missionaries achieved a result quite similar to that of the feminism of the

time: “professional women living independent lives outside the prescriptions of

filial or marital dependency for women provided by Victorian middle-class

culture.” (Haggis, 1998, p. 172).

Alongside what we could broadly term as the patriarchal nature of

monotheistic religions, the discourses and practices of missionaries also prove

problematic due to the obvious power asymmetry from which their relationship

with the pagans to be “civilized” and evangelized gains meaning. Both the

historical-political context and the passionate nature of faith frame what may

have been a genuine conviction that pagans would be “happier” upon converting

to “the true religion” (Stornig, 2013). However, it

is clear that the figure of the infantilized Other who needs to be “helped” and

“saved” was the rationale that enabled the rhetoric of sacrifice and, to that

extent, legitimized these women’s quests and practices for autonomy (Haggis, 1998).

In the case of the Araucanía

Region, Serrano argues: “public education was practically

nonexistent in the area that comprised the province of Arauco until the 1850s”

(1995, 451). The State chose to entrust educational work to Catholic missions

that had accumulated experience since the conquest. After the expulsion of the

Jesuits in 1767 and the prosecution of the Franciscans who resisted the

independence cause, in 1848 President Bulnes negotiated with the Congregation

for the Propagation of the Faith (FIDE) for the sending of the Capuchin order.

These had the greatest impact on the education of Mapuche children at the end

of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries (Azócar, 2014; Serrano et

al., 2018). Thus, after a long history of missionary efforts organized successively by

Jesuits, Franciscans, and Capuchins, the military occupation of Araucanía in

1883 resulted in the Mapuche people being decimated by policies of settlement

and reduction,[3] leading them to practice subsistence agriculture, similarly to peasants.

In this context, the State perceived schools as instruments of civilization,

but they also represented a strategic literacy opportunity for the Mapuche,

offering them some leverage in negotiating land dispossession.

From here, the education of Mapuche girls and boys

would work towards a new cultural and racial (mestizo) pact, which would

redefine gender relations in the Araucanía Region. This redefinition will

determine the strategic role of Mapuche girls as future biological and cultural

reproducers, and to that extent, it will also deliniate the call for Catholic

nuns, Protestant missionaries, and female teachers as educators and

evangelizers.

Interestingly,

the role of women in the educational and civilizing projects of Araucanía has

been scarcely studied. Most research on this matter has focused on the

alliances and influences among men: priests, missionaries, state agents,

chiefs, and Mapuche leaders (Azócar, 2014; Donoso, 2008; Menard & Pavez, 2007;

Montecino & Foerster, 1988; Serrano, 1995).

The present

text will focus on analyzing the discourses of the first German candidates who

applied to the emerging congregation of Catechists of Boroa between 1932 and

1934. Our hypothesis is that in these women’s discourses we can identify

paradoxical strategies which were deployed in the pursuit of recognition and

autonomy.

In

methodological terms, the systematization and cross-referencing work of

archives located in the Araucanía Region -Historical Archive of the Diocese of

Villarrica (AHDV); Archive of the Catechist Congregation of Boroa (ACB)- and

Eichstätt -Magazines Ewige Anbetung and Altöttinger Franziskus Kalender,

Eichstätt-Ingolstadt University, Germany- included letters, magazines, calls,

and other documents in three languages[4]. These were organized into Excel spreadsheets,

transcribed, translated, coded in Atlas.ti, and analyzed from a gender

perspective as culturally coded “texts”, bearers of discourses that coexist and

mutually address each other (Rojo, 2001).

The first part

of the text describes the context in which the congregation arises and analyzes

documents that show how the Capuchin mission summoned and constructed the

missionaries” profile. The second part analyzes letters from the candidates,

highlighting different codifications and self-discursive markings that show

exceptionalism and the tricks of the weak as paradoxical strategies. We will

conclude with a reflection on the limits and possibilities of these strategies,

which constitute part of female genealogies.

Summoning the

Candidates

The origins of the Catechists of

Boroa Congregation can be traced back to 1928 and 1931, after the proposal of

the Capuchin missionary Wolfgang Emslander von Kochel to Guido Beck, Apostolic

Vicar of Araucanía. The foundation of this congregation responded to the lack

of pastoral personnel, explained by Beck using a military metaphor:

[...] the

officers are in their respective posts [...] but we lack junior officers and

combat troops, which are indispensable in a mission territory [...] [We need] a

handful of missionaries and a legion of catechists (Noggler, 1972,

p. 179).

In this regard,

von Kochel argued that the religious instruction of the Mapuche people could

not yet be fulfilled “by the children of the same race” and even less by the

“indigenous catechists” who were trained and between twenty and

thirty-years-old, because “at that age they are already married and have a

family, and thus they no longer move from their hut” (Noggler, 1972, p. 183).

The history of

the Catechists was also linked to the Swiss congregation that had until then

focused its work on the education of Mapuche girls and boys: the Sisters

Teachers of the Holy Cross of Menzingen (HSC). This congregation had settled in

Río Bueno in 1901, deploying its work as prestigious pedagogues across

Araucanía. Such prestige earned them two formal invitations from Santiago to

direct Normal Schools and a dispute between the hierarchies of the Church:

Ángel Jara (bishop of the Diocese of Ancud) and Bucardo de Röttingen (apostolic

prefect of the missions at the time) (Noggler, 1972).

At the request

of the Vicariate, the HSC agreed to train the Catechists both in religious life

and in apostolic activity until 1936.

By 1923, Von

Kochel was the spiritual director of Elsa Metzler, originally from Munich and a

lay catechist in the Boroa Mission. The Capuchin highlighted Metzler’s

“on-the-ground” style in instructing and evangelizing children and adults “from

hut to hut”, a factor from which his proposal would emerge (Noggler, 1972).

In 1932

Teresita Klumpp Streck (daughter of German settlers), Bertina Dachs (Sister

Cecilia), María Baumert (Sister Isabel), and the chilean Juana Norambuena

(Sister Bernardita) joined the first formation of the congregation and took

charge of the first school in Las Dichas.[5] In

1937, Sister Teresita would take the role of superior of the Catechists (Noggler, 1972). The congregation was quickly joined by Chilean and

also Mapuche[6]

women, who evangelized, taught literacy, cared for the sick, and administered

emergency sacraments both in Araucanía and on Easter Island.[7]

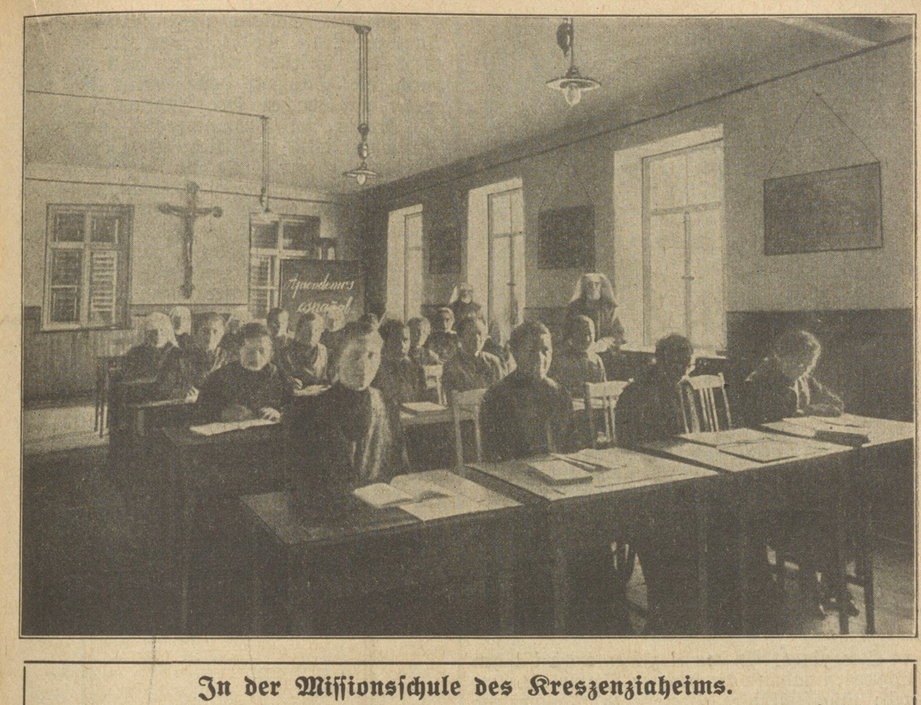

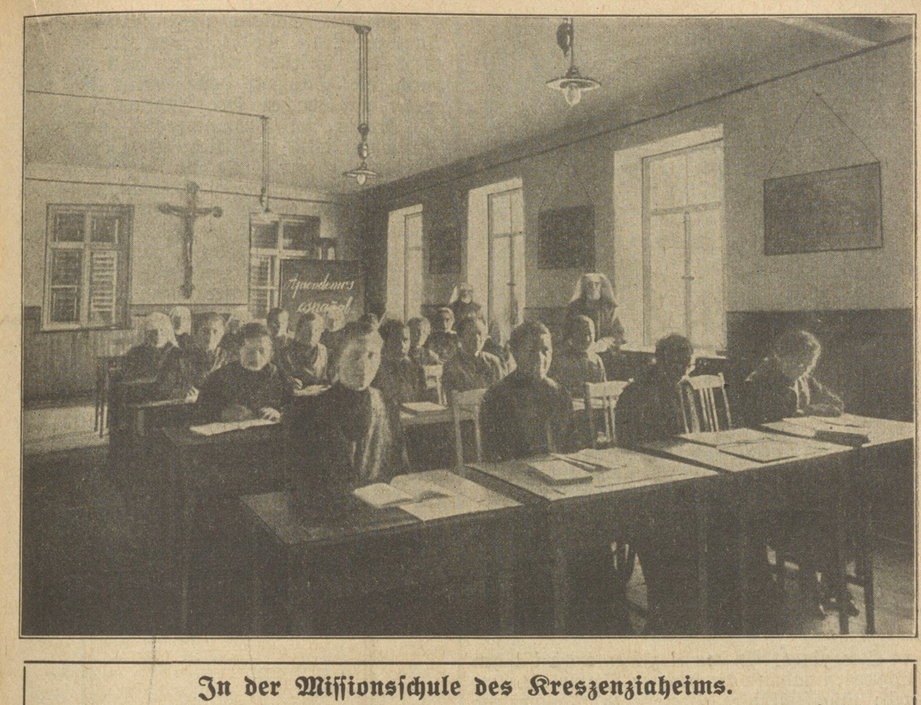

Figure 1. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Meanwhile, in

the devout city of Altötting, a stable relationship had been forged between the

Provincialate of the Bavarian Capuchins of St. Anne’s Convent and the

Kreszentia Mission House of the HSC. It was named in honor of Krescentia Löffer

(1828-1910), a benefactor widow of the HSC who bought the land on which the

mission house was built. Löffer would spend her final years there (Ewige

Anbetung, March Issue, 1910, p. 96).

Before

departing by ship from Hamburg or Antwerp to the Port of Corral-Valdivia, the

candidates received their initial training at Kreszentia House in tasks

directly related to what would be their work in the mission: horticulture,

dressmaking, handicraft, and Spanish classes (Ewige Anbetung, May Issue, 1924, p. 145). In this same house the first candidates selected to

join the emerging congregation were received between 1932 and 1934. In Boroa,

Nueva Imperial, they would be welcomed at the Elisabetinum house (“¡Hacia los ideales de San Francisco y de Santa

Isabel!”, n.d., AHDV), led in its

early years by the Sister of the Holy Cross, Sister Hildegardis (Historical

Archive of the Diocese of Villarrica - AHDV).

Figure 2. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Figure 3. From “Catechist Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the

right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

What was expected of

future missionaries?

The young German women learned about

the Mission in Araucanía through writings that Capuchin priests

addressed to the faithful in Bavaria (Noggler, 1972). The document “The Congregation of Catechists of

Boroa as leaders for Christ” (“Die

Kongregation der Katechistinnen in Boroa als Führerin zu Christus”, n/d,

AHDV), dating around

1932, was addressed to “the benefactors of our beautiful mission in Araucanía”.

This document outlined what was expected of a catechist, the tasks to be

carried out and the living conditions in Araucanía:

From the

Secular Third Order of Saint Francis has arisen a new, ideal and beautiful

flower […] it cannot and should not be a monastic foundation with narrow

limits and nuns in the proper sense of the word […] It is the Congregation

of Catechists in Araucanía, something new of its kind […] Everything is

arranged […] the Elisabetinum in Boroa, the home where these spiritual

troops are trained. It is located in a marvelous place […] with a

panoramic view of the snowy Andes” volcanic range […] a delightful terrain

of cultivated fields, shrubs, and trees, with peaceful indigenous huts

and herds of grazing cattle […] Here they mainly study the two

missionary languages, Spanish and Araucanian, catechism, and biblical

history [...] they are instructed on how to teach both in schools and in huts

[...] Educated in this manner, they become educators of the simple and poor

people around them [...] Their humility must bend the upright pride of

the Araucanian man and straighten that of the downhearted Araucanian woman

[...] Their apostolate should not be loud and strident, but silent and

hidden, like that of a mother in the home, where she never rests [...]

There are already two catechists in the beautiful paradise area of Lake

Ranco [...] one alongside a second lay teacher in Molco, which is very much

disputed by the Protestant sects [...] On Sunday [...] Mass is

celebrated at a distance [...] Weekdays are dedicated to the education of the

men and women of tomorrow, to the children. They are the most

receptive [...] I only wish to add that [the catechists] actively

participate in the administration of all the sacraments [...] They are even

involved in the sacrament of Holy Orders, as they seek authentic vocations

everywhere [...] In the chapel, they faithfully care for beautiful folk

singing, keep the sanctuary clean and orderly, and take care of the cleaning

of the church. In the cabins, the sick and dying are prepared to receive

the sacraments and eternal life. A sacred fire burns in these religious

women consacrated to the service of God in the world, a fire of blissful

joy, [...] When the awareness of saying “I am a missionary, I am at the

service of the struggling, suffering, and triumphant Church, I must fight and

suffer for God’s cause, even if only as a poor and weak instrument in the hands

of the Almighty” [...] sinks deeply into the soul, it becomes clear that

one must forget, so to speak, personal demands, homeland and mother tongue,

comfort, and local customs [...] in order to gain the trust of those

whom one wishes to bring to the beloved God. Chileans and Mapuches are

especially easy to win over when they see that one is like them [...]

German girls should not believe that they can simply walk around the cabins

[...] It is not that easy [...] they must show concern for the care

of the sick, set a good example, perform acts of love, be receptive to

the desire for religion, and, without emphasizing their superiority,

they must humbly and with caution and kindness immerse themselves in the

new environment [...] And surely it would be a sublime, longed-for, and

radiant grace for centuries to win over for the humble faith and Christian life

the proud and self-sufficient Araucanian people. Their conversion would be

worth the sweat of the noblest (“Die Kongregation der

Katechistinnen in Boroa als Führerin zu Christus”, n/d, AHDV).[8]

Although it is

not possible to identify the author of this call or exactly how it circulated

in Germany, it was most likely drafted or at least reviewed by Beck himself. It

should be noted that secondary sources describe Beck as an extremely

detail-oriented man (Noggler, 1972; Umbach, 2017). In any case, this first call, drafted by Capuchin

missionaries, envisions for this “new in its kind” work women who are not

necessarily nuns. They were to be women of faith who had to be willing to

“forget” their homeland, language, comforts, and customs, who had to tolerate

“Mass at a distance”, learn two languages, and work diligently for the pagans

and the Church. The call also offers a whole series of proposals for

identification, from the “marvelous landscape with a panoramic view of the

snowy Andes volcanic range”,[9]

to a model of feminine epic (“struggling, suffering, and triumphant”) that

articulates sacrifice and humility but also power (administrators of

sacraments, evangelizers of a proud people, soldiers fighting against

Protestant sects).

Stoler (2004) argues that concerns about the distribution of

sentiment (its excess and its lack), by control techniques and affective

modulations, characterized (post)colonial European administrations. Such

concerns were not only aimed at the subjects to be civilized, but also at the

most vulnerable representatives of European power: poor whites, “mixed-race”

children, and women. By making cultural and gender expectations explicit, the

call outlines a whole series of “correct feelings” for the future missionaries.

This way, it is expected that they will organize, clean, sing, and care “like a

mother who never rests” but in whom also burns “a fire of blissful joy”.

Through a female apostolate that is “silent, hidden, humble, cautious, and

kind” that does not “emphasize their superiority”, the missionaries must “earn

the trust” of the pagans, “show concern” and “be receptive”.

Considering the

strategic racial and cultural place held by these women as symbols and models

of “good femininity” in the missionary project, the call outlines the norm of

legitimate femininity: the domestic ideal is articulated with the rhetoric of

female moral superiority through modulations of what constitutes correct

feelings, of what is shown and what is hidden to convert the pagan Other. From

this “silent” and “loving” female superiority, great rewards could be expected:

the conversion of the “proud and self-sufficient Mapuche people would be worth

the sweat of the noblest”.

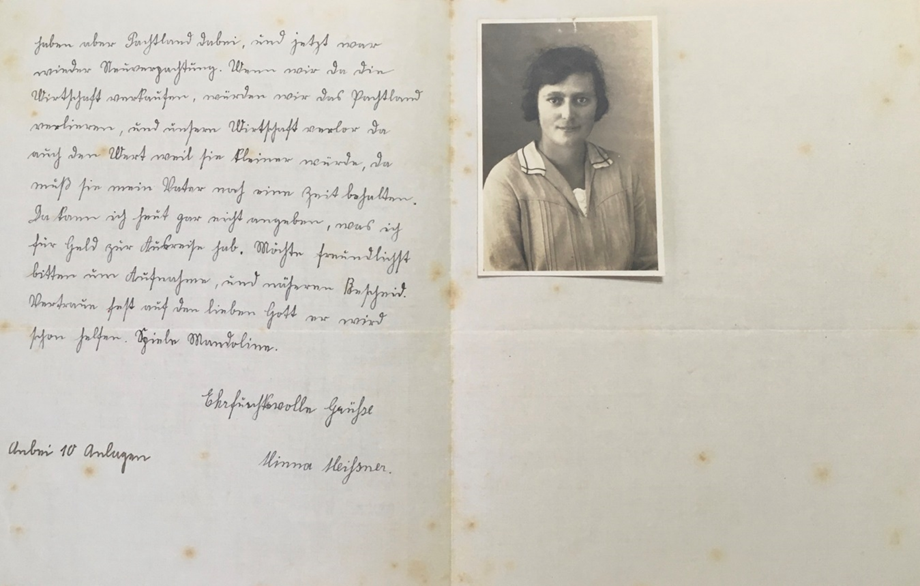

On the other

hand, the document “Greetings from God!” (“Gott zum Gruss!”, n/d, AHDV) drafted by the Missionary Secretariat of the

Capuchins of the convent of Santa Ana in Altötting, mentioned that “once their vocation

has been clearly understood through fervent prayers and mature reflections”,

a series of certificates should be sent: medical, birth, baptism, confirmation,

completion of primary and/or secondary school, of singleness, of “release,

officially sealed by the convent superiors, in case they have belonged to an

order or congregation as a postulant, candidate, novice, or sister. The

certificate should also indicate the reasons for their exit”, a “certificate

of good conduct enclosed by the corresponding parish priest”. And also a

“handwritten autobiography”, “attached questionnaire, completed truthfully, and

a photograph”.[10]

The document

also requested covering at least part of the travel expenses (800 marks) and “depositing

any owned property (at least 3,500 marks) in Chile. However, given the current

uncertain circumstances, (“Gott zum Gruss!”, n/d, AHDV)[11] we advise not to make any arrangements in this regard

without consulting with the Apostolic Vicariate first”. Likewise, it was

suggested to maintain “insurance in case of illness or disability, at least

during the two-year probationary period”. The document specified that Bishop

Guido Beck would be responsible for the admission decision: “the final

notification will be received, along with detailed instructions for traveling

to Chile, in approximately three months. Until then, spiritual preparation

for the missionary vocation should be the most prioritary and important task”

(“Gott zum Gruss!”, n/d, AHDV).[12]

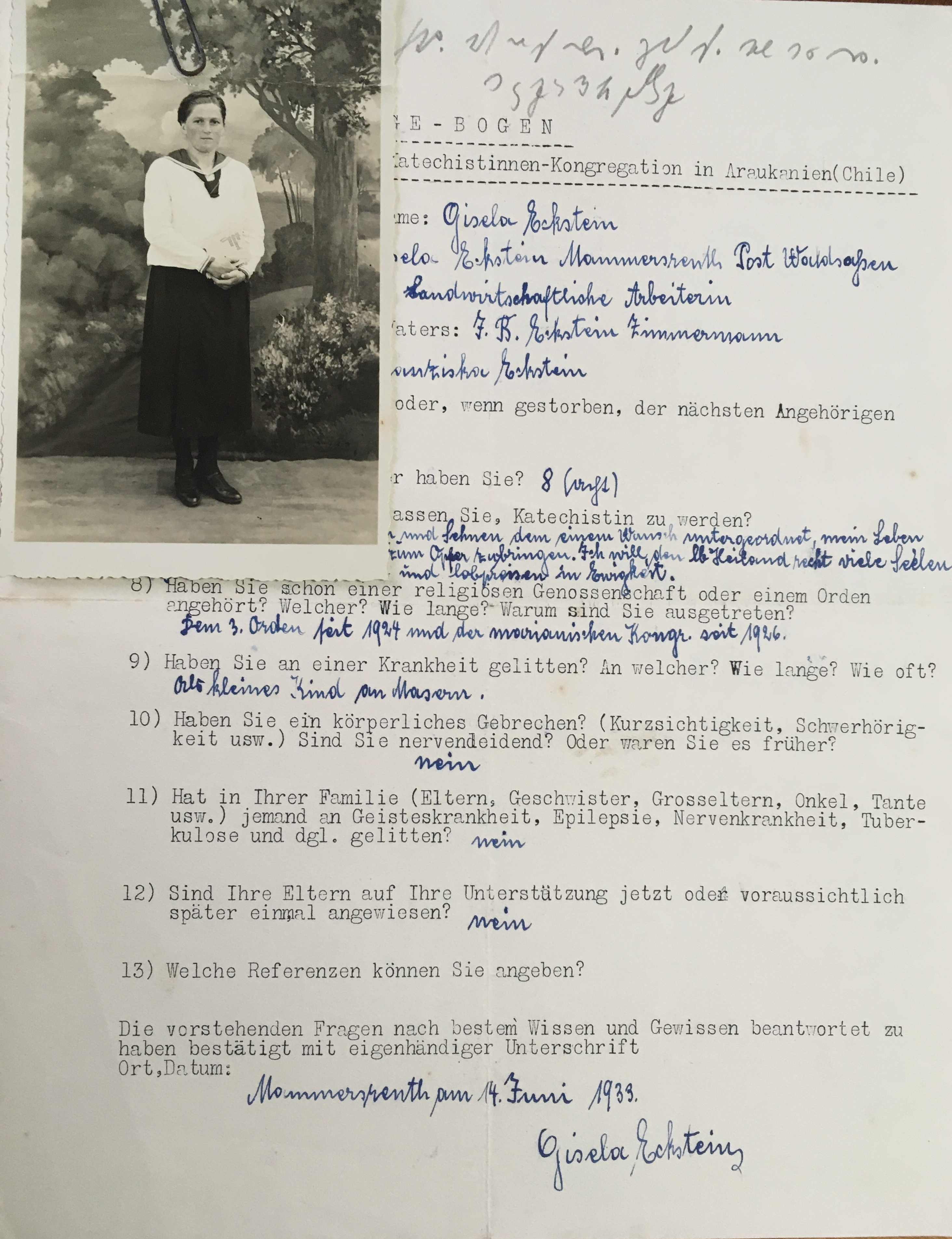

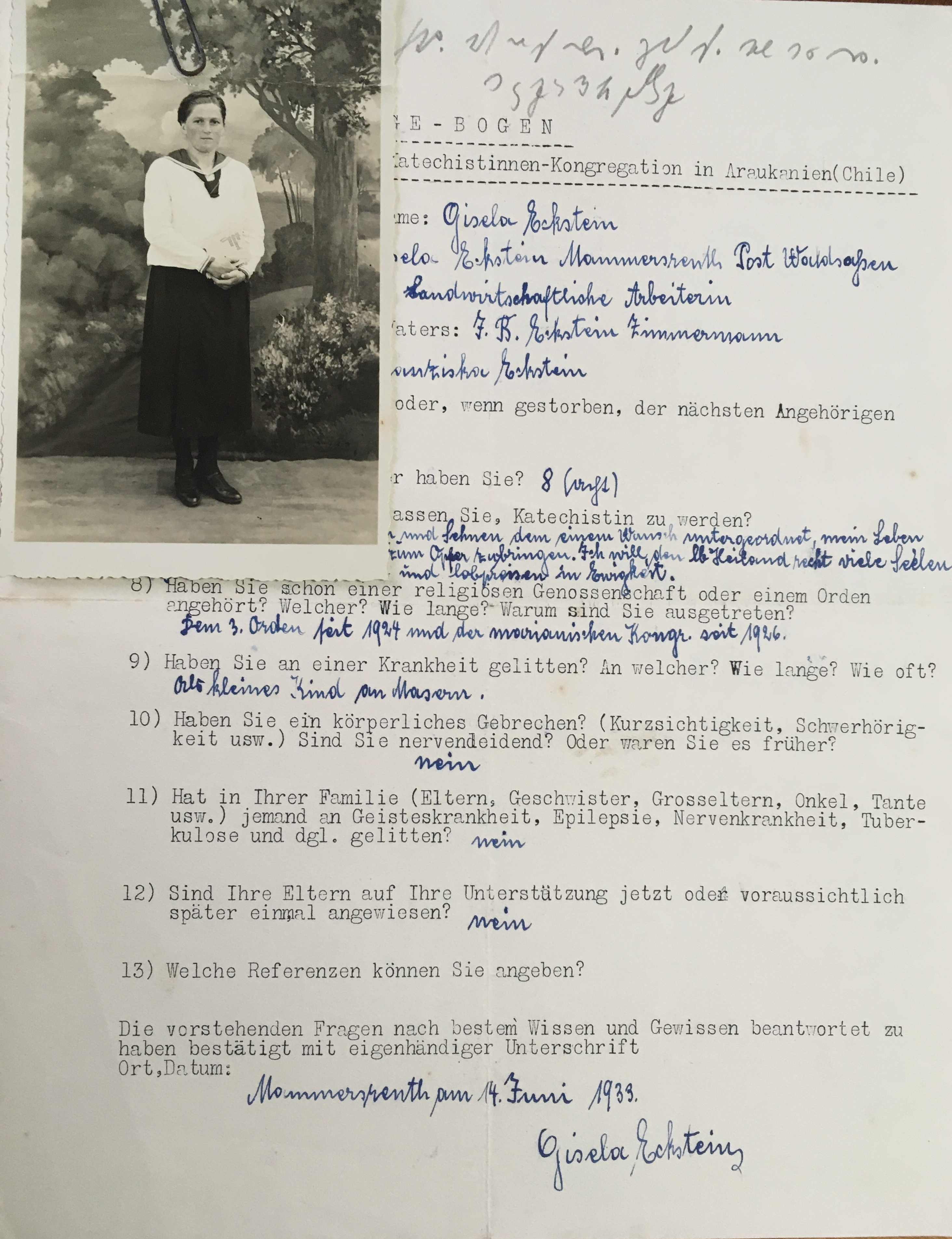

Some of the

questions from the questionnaire attached to the application are also

interesting to highlight: “What are the reasons that lead you to want to be a

catechist?”, “Physical disabilities (myopia, deafness, etc. Do you suffer from

nerves? Or have you suffer from them previously?)”, “Mental illnesses or others

(epilepsy, nervous diseases, tuberculosis) of direct family members”, “Current

or future dependence on your parents” (“Fragebogen für Bewerberinnen zur Katechistinnen-Kongregation in

Araukanien (Chile)”, n/d, AHDV).

In the

“Declaration”, signed by their own handwriting, candidates affirmed their

voluntary entry into the congregation, whose main task was “the pursuit of personal

sanctification” as well as “teaching religion to young people and adults”,

adhering to “the Rule of the Third Order of Saint Francis of Assisi, together

with the simple vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity” and submitting

to “a trial period of two years, consisting of one year of postulancy and

one year of novitiate, and after that time, making annual vows for six

years to finally making perpetual vows”. They also agreed to “cover the

travel expenses to the mother house in Boroa” and in case of “leaving

the congregation before making perpetual vows”, “to reimburse, to

the best of my ability, the expenses incurred by the congregation on my behalf for

the journey to Chile and back” (“Erklärung”, n/d, AHDV).[13]

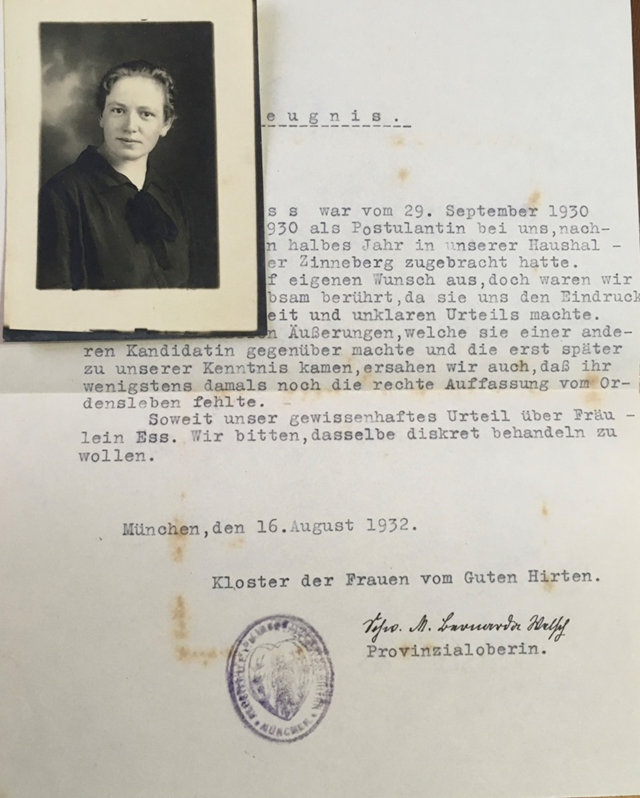

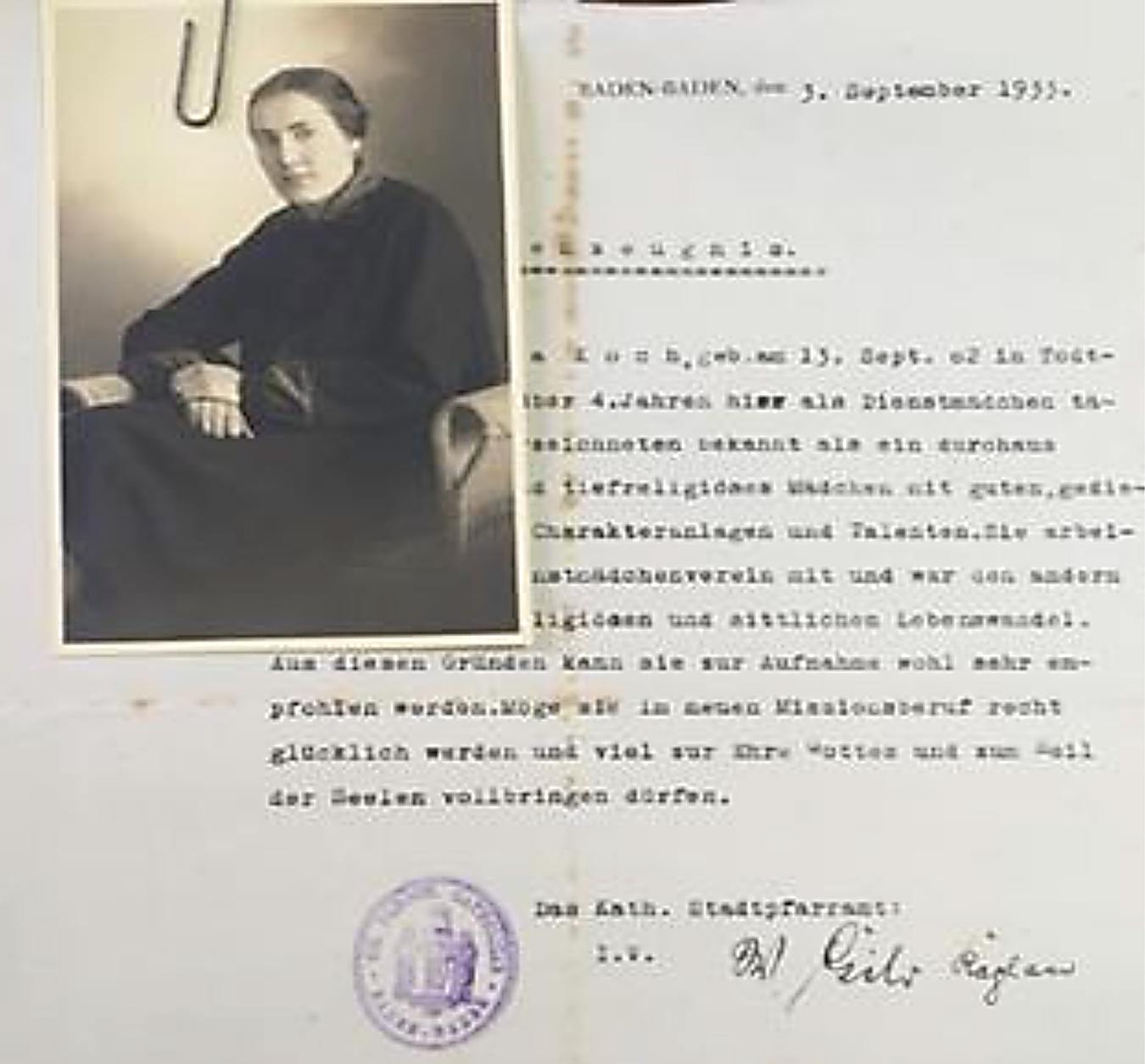

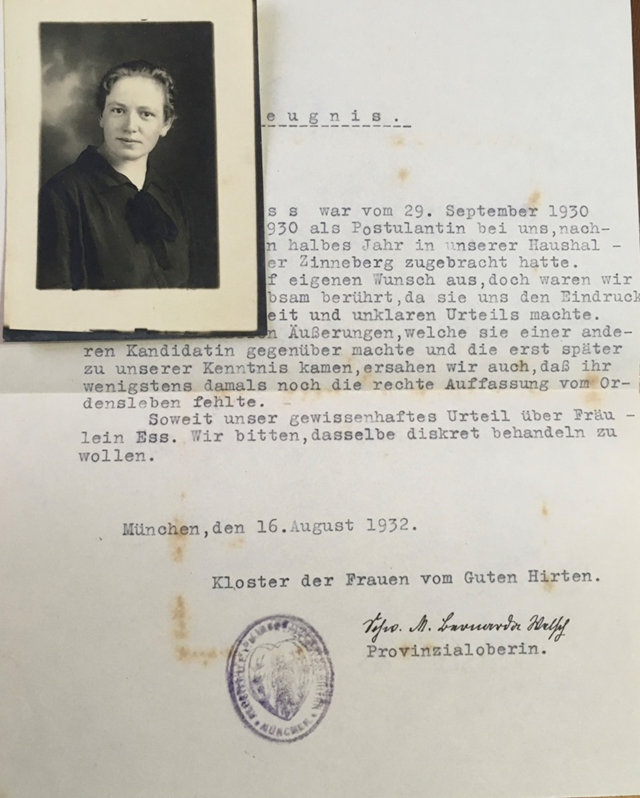

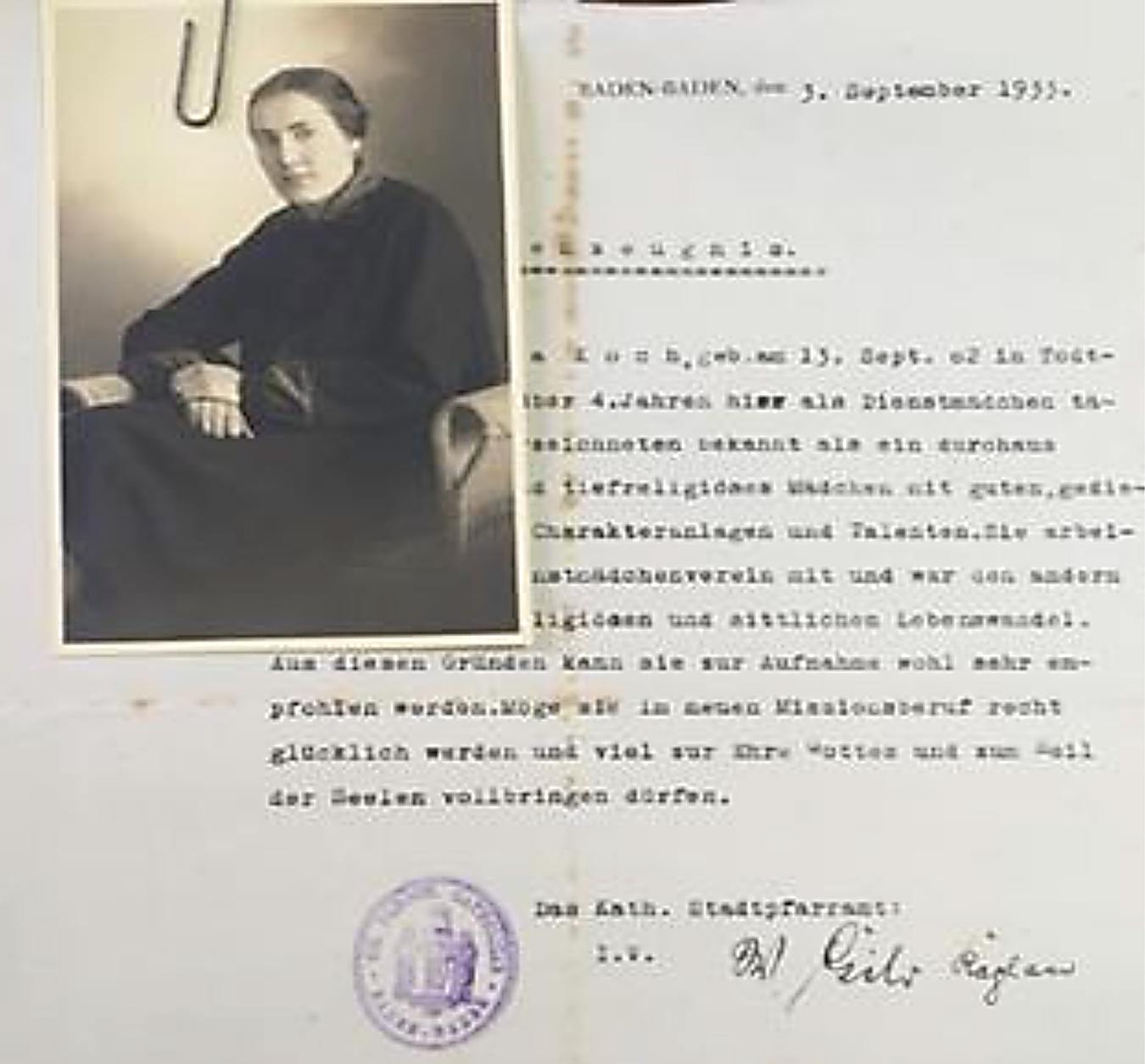

Other key

documents included in the application dossier were the “references” that

accredited work or pastoral experience and the “certificates of moral conduct”,

usually provided by the parish priest from the town where the aspirant resided.

Here, it is possible to identify common institutional codes regarding the

candidates” character, judgment, or disposition, highlighting characteristics

such as: “very apprehensive”, “unclear judgment”, without “adequate

understanding of religious life” (Sister

Superior Leonarda Welsh, 1932, AHDV), “conscious and with character” (Sister Superior Engelmann, 1932, AHDV), “solid, mature, and firm character qualities” (Father Räglau, 1933, AHDV).

Figure 4. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Priests and

nuns also emphasized, when applicable, the aspirant’s participation in Catholic

women’s organizations such as: the “Institute of English Ladies” (Sister Superior Engelmann, 1932, AHDV), the “Association of Catholic Domestic Workers” (Father Räglau, 1933, AHDV), or the “Association of Marian Virgins” (Pastor K. Arnow, 1932, AHDV). Reputation was also a relevant indicator,

highlighting the quality being an “exemplary virgin” (Parish office of Saarbrücken, 1932, AHDV), of “impeccable reputation”, deserving of “the trust

of her superiors” (Father

Caedilian, 1933, AHDV) or the “lack

of inclination” towards “worldly pleasures”, nor “contact with persons of the

male sex” (Pastor K.

Arnow, 1932, AHDV).

Figure 5. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige

Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p. 148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Finally, the

“guarantee of a true vocation” (Parish office of Saarbrücken, 1932, AHDV) in the candidates was identified based on a “weekly”

or “daily” frequency of confession and communion (Father Caedilian, 1933; Pastor K. Arnow, 1932, AHDV), the presence of the “longed-for missionary ideal” (Sister Superior Engelmann, 1932, AHDV), their election “of supernatural reasons” (Father Caedilian, 1933, AHDV), the potential to “accomplish much in honor of God

and for the salvation of souls” (Father

Räglau, 1933, AHDV) or the

“chaste, constant, and serious pursuit of perfection” (Parish office of Saarbrücken, 1932, AHDV).

Figure 6. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

The application

of the young women was closely monitored by Father Eduard[14]

from the Convent of Santa Ana in Altötting and by Vicar Guido Beck in San José

de la Mariquina. Concerns about money and the socio-political crisis permeated

that exchange of letters.

Father Eduard

expressed his concern about the candidates” economic and health conditions,

considering what National Socialism could mean for the funding of missions:

It is important

to clarify how sisters are cared for in case of illness or old age [...]

We expect terrible things from the Third Reich [...] our

well-informed sources predict devaluation under Hitler [...] I beg

[...] to return all certificates, as people may also need them to obtain

authorization for exit or entry (Letter from Father Eduard to Guido

Beck, 1932, AHDV).[15]

Beck responds

rather more concerned about the funding of travels:

I wish you to

take as a general rule that nobody will be able to come until they have at

least half of the travel fare. If people have to pay for themselves, there

is already some guarantee that they will take the matter seriously and stay.

What costs is more valued (Letter from Guido Beck to Father Eduard, 1932, AHDV).[16]

Two years after

this exchange, we find ourselves in 1934 with a distressed Father Eduard

proposing to reevaluate the relevance of continuing to offer German candidates

to the congregation:

Is it really

necessary to hire German girls after abandoning the previous plan of forming

a congregation of sisters without vows? [...] Couldn’t local forces try

to be recruited with the considerable sums that must be spent on transportation

and care of German girls, especially after enough Chilean women have

already shown up and considering that there are already German sisters who

can balance the situation? [...] The current mode of accepting people is

completely unsustainable. We have only been spared by a fortunate coincidence

of avoiding transporting someone with tuberculosis, mental illnesses, or

divorced with questionable backgrounds (Letter from Father Eduard to “his Reverence”, 1934, AHDV).

In this

exchange of letters, we also identify examples of Beck’s criteria for selecting

candidates: “has talent. Knows a foreign language. Has very good

recommendations. Has 500 marks”, “pious”, “years in a girls’ education school

[...] Firm character. Good age: 24 years. Has resources”. And also, his

elimination criteria: “she is very poor and does not have much education or

talent”, “she is too old (41 years)”, “she was already with the Good Shepherds.

She couldn’t handle it” (Letter from Guido Beck to Father Eduard, 1932, AHDV).

Beck’s

missionary profile implied the twenties as the ideal age, health, good

certificates, ideally not having been and/or left other congregations, and

possessing some education. His insistence on the issue of money for the trip

seems justified not only by the constant struggle for Mission funding but also

as a show of solidity in the candidates: “what costs is more valued”.

On the other

hand, in the critical context of Hitler’s rise to power, we can identify a

sense of responsibility from Father Eduard for the economic fate of the

candidates in old age and illness and also for concrete details such as the

cost and practical value of certificates. However, his reluctance to continue

sending German candidates was also justified by a certain distrust in the

selection process, whose vulnerability could lead to problematic choices of

young women “with tuberculosis, mental illnesses, divorced with questionable

backgrounds”. Probably to reassure Beck (with whom he seems to share a

certainty about the cultural superiority of their common homeland), the priest

adds that “recruiting local forces” would not be a bad idea considering that

“there are already German sisters who can balance the situation”.

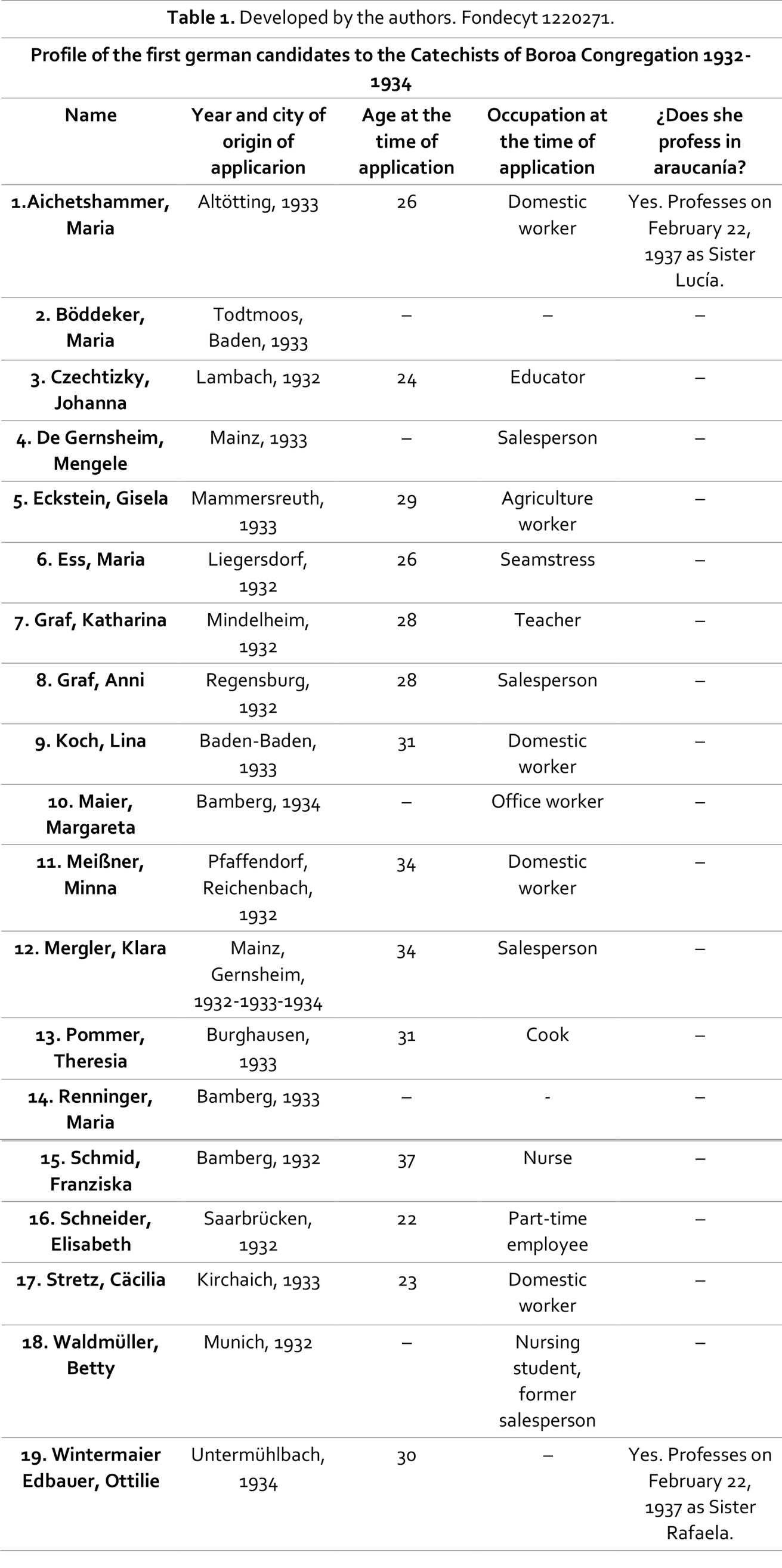

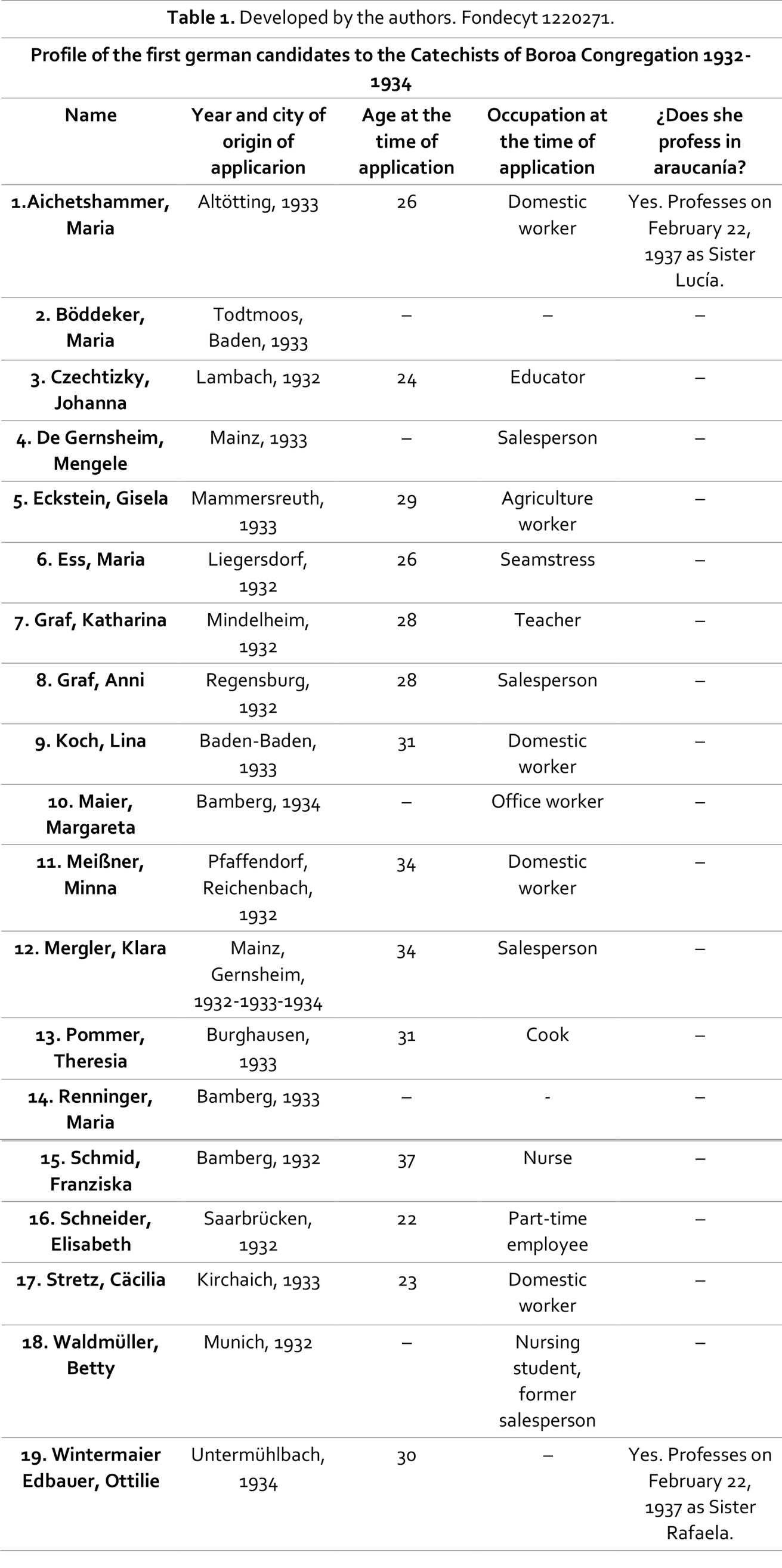

Based on the

systematization, cross-referencing of files, and secondary sources, (“First candidates to the Catechists of Boroa

1932-1934”, AHDV; “Date of birth and religious profession of the missionary

catechist sisters”, ACB; Noggler, 1972) we have generated the following summary table of the

candidates” profile (Table 1):

Paradoxical strategies

Exceptionalism and

border crossing

Mobility as a force of identity

transformation holds a gendered history that speaks of practices that open and

close possibilities for creativity, agency, and autonomy (Ahmed, 2017; Dorlin, 2003; Stornig, 2013; Vera &

Sáez, 2022). Stornig (2013) asserts that missionary nuns” (self)representation as

“essentially mobile figures” demonstrates how the practice of crossing

geographical borders through travel also transforms into a crossing of gender

borders.

Young

candidates responded enthusiastically to the promise of being “mobile

ambassadors of an expanding Church [...] bringing faith to non-Christian

peoples” (Stornig, 2013, p. 94), invested by a

“fighting, suffering, and triumphant” Church.

The dossier’s

“autobiographies” were young women’s presentation letters, in which, along with

facts from their lives, we could identify desires, silences, and

self-representations that we propose to read under a strategic discourse

framwork.

As we can see

in Table 1, those who write are Catholic women living in a predominantly

Protestant country, residing in rural areas, from poor or impoverished

families, single, with basic levels of education, and limited prospects for

stimulating employment. Their country had recently experienced a war in which

some relatives had already perished, and was undergoing economic, political,

and social crises, moving towards the Nazi regime.

Lina Koch, for

example, tells us:

In 1910 [...] I

still had three brothers and four sisters. My older brother died in 1913 in

the novitiate of the Capuchins in Bolzano at the age of 19 [...] In

1917, my second brother died in the war [...] Then, I spent a year in

Switzerland working in a large farm. However, as the entire region was

Protestant, I suffered greatly [...] My second sister also got married, so

I had to take over the household chores [...] I got a job in Baden-Baden,

as I wanted to learn to manage a high-class home. A year later, my

mother fell ill, and I returned home to take care of her [...] I still

couldn’t leave my home (Lina Koch, 1933, AHDV).[17]

The letters

reveal a difficult time in which death, war, poverty, caring for sick family

members, and hard work define these women’s life experiences. In that context,

and similarly to the Capuchins, the women express concern about the costs of

the journey:

For a long

time, I have had the desire to serve beloved God in a convent as a nun [...] My

parents are very poor, they have six children and all of them are still young [...]

they depended on my income. But when God calls, He also clears the way. Two

of our dear little ones are already in heaven and now it is more possible for

me to enter [...] I do not have a high school education, but that should

not be so necessary, I believe I have enough knowledge and the beloved Savior

has provided me especially with courage and sacrifice. But I must repeat

what I mentioned at the beginning, we are poor, and my parents can’t give me

more than what is necessary in terms of clothing (Elisabeth Schneider, 1932, AHDV).

I want to go on

the mission with all my heart and soul, to win many immortal souls […] It

is said that each candidate should strive to cover half of the travel

expenses. Unfortunately, I cannot ask my parents, after all they have done

for my education, to give me now 400 marks […] They can barely make

ends meet and cannot save any money (Maria Renninger, 1933, AHDV).[18]

I may have some

difficulties with the travel expenses, if they must be

covered at the time of entry. We do not have cash and my father is a war

veteran with a very low pension (Gisela

Eckstein, 1933, AHDV).[19]

These

experiences emerge as background to the manifestation and modulation of the

desire to depart to a country they do not know, probably never to see their

homeland or family again. In this context, the magazines Ewige Anbetung

and Altöttinger Franziskus Kalender play the important role of enabling

the imagined projection of another life, an illusion that takes the form of a

missionary vocation expressed vehemently:

I wanted to be

a missionary nun or join a contemplative order [...] I read

in the new Altöttinger Franziskus Kalender the call to healthy and generous

girls who wish to serve the beloved Savior in the indigenous mission. This

seemed to me a sign from God, as I immediately felt a great desire to follow

this vocation. And now I am turning to you with trust, asking to be

admitted to the newly founded Congregation of Catechists. I am 22 years old,

healthy and strong (Elisabeth Schneider, 1932,

AHDV).

A few weeks

ago, I received the latest issue of Ewige Anbetung and found the

article about the Catechist Missionaries in it. I only have the desire to

become one of them as soon as possible. I also firmly believe that I am

suitable for it [...] Ever since my childhood I have had the desire to

enter a convent and at the age of 14, the missionary vocation awakened in me

[...] I am full of energy and enthusiasm to work. [...] I beg you,

please, to shorten the waiting time for a response and write to me as

soon as possible. They have already given me all kinds of appetite

stimulants, but I know that I will not be able to enjoy food or anything if

I do not find a place soon [...] I am willing to give everything a young woman

can give (Maria Renninger, 1933,

AHDV).

The reverend

told me that if I had such lofty ideals, I should wait patiently, pray much to

recognize God’s holy will and not hesitate to respond [...] When I received the

brochure from Ewige Anbetung in February, I was immediately excited

and could not keep still. I have only one desire [...] to be able to

dedicate myself to this noble vocation [...] After careful reflection

and fervent prayer, I have decided to embrace the profession of catechist [...]

May the Sacred Heart of Jesus grant me the strength and grace to assume with

great courage this difficult life of sacrifice (Lina Koch,

1933, AHDV).

Figure 7. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Passionately

so, the young women say they are “excited”, “unable to stay still”, “feel a

great desire to pursue this vocation”, want to depart “with all their heart and

soul”, “cannot even enjoy food or anything” until they have the certainty of

being accepted, asking for the “waiting time for a response to be shortened”.

Even the end of family dependence that hindered their departure is interpreted

as part of divine design: “two of our dear little ones are already in heaven,

and now it is more possible for me to enter”.

To the

historical and political conditions that may have shaped the desire to depart,

it is also important to add that Catholic young women seem to have been

attracted by the proposal of epic identification offered in the calls,

therefore producing the corresponding self-representations: “to bravely take on

this difficult life of sacrifice”, “the beloved Savior has provided me with

special courage and sacrifice”, “I want to win many immortal souls”.

With insight,

the young women read between the lines that the desire to depart should not be

presented in their letters as mere anxiety, and to that extent, they make sure

to point out that such desire has been the product of discernment, of “careful

reflection and fervent prayer”, of “praying much to recognize God’s holy will”.

In a coded

language of sacrifice, courage, vocation, discernment, character, and absolute

commitment, the candidates” letters constitute a moving example of a

paradoxical strategy in the quest for recognition that we propose to read as

exceptionalism.

Riot-Sarcey and

Varikas affirm that this strategy “lurks in female and feminist writings” and

is often “at the origin of the paths taken by self-affirmation” (Riot-Sarcey & Varikas,

1988, pp. 79-80). Thus, “insofar

as the free human being is from the outset and by definition situated at the

antipodes of being a woman, access to this status is only possible through a

constant and systematic effort of differentiation in relation to the gender of

women ... : “I am not like all women” [...] dissociating oneself from members

of one’s gender is the “guarantee” [...] that the exceptional woman seems to

owe to patriarchal society” (Riot-Sarcey & Varikas,

1988, pp. 82-86).

Elisabeth Horán

argues that in the hostile sociopolitical framework of national fraternity in

which the body is the obstacle to recognizing women as citizens, the rhetorics

of female exceptionalism will strive to appeal “to the importance and value of

women outside the sexual sphere” (Rosa, 1996, p. 98). Comparatively analyzing the use of this strategy and

its self-markings (habit, mask, armor, uniform) in the “rhetorics of sanctity”

of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and of Gabriela Mistral, Horán affirms that

exceptionalism is usually configured by a series of “carefully coded” masks in

which suffering, persistence, humility, self-denigration, and sacrifice allow

for the representation of female heroism and victory over one´s own flesh.

In the case of

the missionaries, the quests for recognition and autonomy through the material

and symbolic crossing of borders depended on investing a racial, cultural, and

gender hierarchy among women. Differentiating oneself from “women in general”

by sacrificing oneself for “the pagans” seems to be, then, the double movement

of this heroic saga. Like the uniform and armor of celibacy, the habit and veil

that would clothe them when taking their vows would constitute “the social

skin” of celibacy, the key to Catholic female exceptionalism (Stornig, 2013).

Tricks of the weak

The careful modulation of what is

said, what is not said, and how what is said is said emerges as a crosscutting

anxiety in the letters of the candidates. We propose to interpret this anxiety

in light of what Ludmer - analyzing Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s “Reply to Sor

Filotea” – refers to as tricks of the weak:

Knowing and

saying, demonstrates Juana, constitute confronted fields for a woman; any

simultaneity of those two actions entails resistance and punishment [...] In

this double gesture, the acceptance of her subordinate place (women should keep

their mouths shut) and her trick combine: knowing but not saying, or saying

she doesn't know and knowing, or saying the opposite of what she knows.

This trick of the weak, which here separates the field of saying (the law of

the other) from the field of knowing (my law), combines, like all tactics of

resistance, submission and acceptance of the place assigned by the other, with

antagonism and confrontation, withdrawal of collaboration (Ludmer, 1985, pp. 48-52).[20]

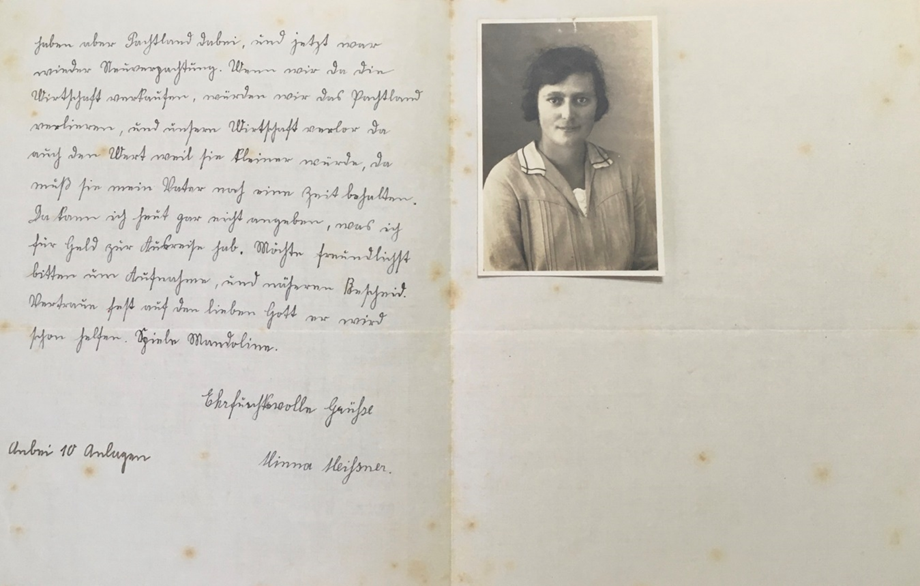

The modulation

and negotiation of anxiety, however, did not always succeed. Such was the case

of Klara Mergler,[21]

who despite applying in 1932 with recommendations that highlighted her “solid

character”, that she is “hardworking and deeply religious”, “modest”, of “noble

discretion”, that she “attends daily Mass in our church” (Father Johannes, 1932, AHDV), that her “reputation”, “behavior”, “moral and

religious conduct were always excellent” (Father Feuerbach, 1932, AHDV), is not selected. Mergler will write letters from

1932 to 1934 requesting explanations and insisting on her admission. The

priests involved in the process interpreted this as “extravagant” stubbornness,

emphasizing “how little can be trusted in recommendations and references, even

from confessors” (Letter from

Father Eduard to ‘His Excellency’, 1933; Letter from Father Eduard to Guido

Beck, 1934, AHDV). Somewhat more

indulgent, Father Suitbertus explained:

[...] the

good girl already had many hopes placed in her work as a catechist among the

pagans [...] I could hardly understand her rejection [...] I

would like to ask you to write her a few lines personally and clarify to her

why, according to your assessment, she can no longer be considered suitable for

the mission (Father Suitbertus to

Father Eduard, 1933, AHDV).[22]

Mergler’s

remarkable determination is interesting to think about as one of the forms that

the desire to depart acquires:

In response to

your esteemed letter, Your Excellency, most worthy sir, I cannot allow myself

to make any judgment, as I am not allowed to know in what sense it is to

be understood [...] Also in my homeland I want and can do much good, and I have

shown it; but I do not love half measures; I want to devote myself

completely to the beautiful missionary vocation. However, I am not given

that opportunity here [...] I have great self-esteem and willpower [...]

with the grace of God and my own effort, I will overcome this obstacle

indeed [...] I have reflected my spiritual state of mind in a simple and

modest way; I am not a saint [...] I repeat [...] I wish to be

admitted as a candidate to the Congregation of Missionary Catechists [...]

My last confession [...] I have failed in the love of God by not preventing

the diversion of my disorderly thoughts [...] I had especially intended

to break my own will and master my self-love [...] Mercy, my Jesus. I

ask for repentance and absolution (Letter from Klara Mergler to ‘His

Excellency’, 1934, AHDV).[23]

In this letter

addressed to “Your Excellency”,[24] Mergler tries to navigate a fluctuation of emotions.

Strategically, Klara does not directly question the decision and instead

confirms that she would not be qualified to pass judgment or “know”. Klara

“knows” but says “does not know”. There are also things she does not “say” but

“knows”, she “knows” there is something unfair about her situation, and while

she accepts the suggestion to deploy her apostolate in her own country, she

also emphatically marks her will and identity: “I do not love half measures”,

“I am not a saint”, “I want to devote myself completely”, “I have great

self-esteem and will”, “with my own effort, I will overcome this obstacle”. And

while those gestures of self-affirmation “say” her strength, simultaneously,

Klara denies it. She submits, repents, asks for forgiveness: “I had intended to

master my self-love”, “I have failed to avoid the diversion of my disorderly

thoughts”, “I ask for repentance and absolution”.

This

fluctuation shows the helplessness in the face of the denial of “an

opportunity” to embody the proposed epic, an injustice experienced turbulently.

In what is evidenced as an internal battle against this helplessness that has

lasted at least two years since her application, Klara closes her letter

admitting defeat.

Paradoxically

so, the “weakness” of these “tricks” that avoid direct confrontation coexists

with the candidates” great confidence in their strength, courage, and capacity

for work:

Regarding the

learning of the two languages, I suppose it won’t cost me my head. If others

can do it, why couldn’t I also achieve it? And I am not scared of work either (Gisela Eckstein, 1933, AHDV).[25]

Figure 8. From “Catechist

Missionaries in Boroa, Chile. On the right, their Teacher: Father Wolfang”.

Note: Ewige Anbetung, April Issue, 1933, p.

148. Library of the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

The candidates

are convinced of “being fit”, being “qualified”, being “healthy and strong”,

“not being afraid of work”, being “full of energy and enthusiasm for work”,

“willing to give whatever a young woman can give”.

However, the

sharpness with which the candidates identify and shield their aplications” weak

points also reflects a strategic awareness marked by ambivalence. For example:

I do not want

to hide that I was already a candidate at the home of the

Sisters of the Holy Cross in Altötting [...] I was dismissed from

there for once expressing that I had insomnia at night. They took that

statement so seriously [...] I still regret very much today having

made that statement in my sincerity at the time [...] My most fervent

desire is to be able to work soon in foreign missions and I will not stop

praying for this great grace (Margareta Maier, 1934, AHDV).[26]

I intended to

join the Sisters of Mary. I sent the required documents, but they were returned

to me with the observation that they do not accept people who have been in

another convent before. It hurts so much to hear that. If I had committed

any offense, I could understand it (Maria

Renninger, 1933, AHDV).[27]

I am 37 years

old. For 14 years, I have been a nurse [...] I was in Sofia, Bulgaria, also

in Romania and Turkey from 1923 to 1927 [...] I wanted to enter a monastery

[...] but unfortunately my father and brothers did not allow it [...] I

am aging and the thought of completely surrendering to God and offering my

strength and health to others does not leave me in peace. My spiritual

guides tell me that I should not lose hope, since there are also late

vocational priests, so why wouldn’t God take me as a nun in my more mature

years for his service? [...] My current work is very unsatisfactory and

boring, as I am taking care of a young lady who suffers from spinal cord

disease and also taking care of the whole household (Franziska

Schmid, 1932, AHDV).[28]

My grandfather

had a brewery [...] where supposedly my mother’s brothers would have spoiled

themselves with a cold drink in the summer [...] My mother has always been

healthy [...] as well as my brothers and I [...] Therefore, it seemed to me

somewhat insignificant and I did not mention anything about it when I was with

you, because all that happened ten to fifteen years before I was born [...]

I even spent money and had an X-ray examination to make sure, with a

very competent and sought-after surgeon [...] I can even send you the X-ray

that I took if you want to check it [...] Please forgive me, I did not

want to hide this matter [...] I just ask you not to reject me

immediately. Please let me know if I can still be admitted (Ottilie

Winter Maier, 1934, AHDV).[29]

It is quite

clear that the candidates are aware that they are not only object of

examination but also of suspicion. We propose that the candidates identified in

the incisive questions of the questionnaire and the requirement for information

about belonging to other congregations, their dependence on parents, health,

and illness; the institutional codes against which they had to armor

themselves, explicitly stating that they did not want to “hide” information

such as the illness of a family member’s or having been in another convent

before. The attempt to ward off suspicion and become worthy of trust would be

to be sincere, apologize, show oneself.

Ottilie Winter,

who will finally profess in Araucanía as Sister Rafaela, not only apologizes

but also offers the evidence of her body (an X-ray) as proof of sincerity and

repentance. This gesture of self-exposure could be read through what Rivière

called “femininity as a masquerade”. Faced with the terror of being discovered

and punished for believing to possess or know something that dominant

masculinity does not possess or know, women can manage the anguish “by

pretending to be castrated women or innocent and harmless creatures [...] just

as a thief empties his pockets and asks to be searched to prove that he has not

stolen anything” (Rivière, 1929, p. 221).[30]

Other

candidates show some disagreement with the standards that would negatively

label the fact of having belonged to and left other congregations: “I regret my

sincerity back then”, “if I had committed any offense, I could understand it”.

Meanwhile,

faced with the urgent requirement of paying for the trip, Margareta Maier turns

the age standard to her advantage: it would not be convenient to wait longer

“due to my advanced age”. In turn, aware of her aging, the globetrotter

Franziska Schmid requests equity by appealing to the institutional authority of

her spiritual guides who would have encouraged her “since there are also late

vocational priests”. Even more astonishing, and we dare to speculate that

precisely because she has already crossed geographic borders (Sofia, Bulgaria,

Romania, Turkey), Schmid crosses gender boundaries and “says” what should not

be said: boredom and personal dissatisfaction also represent motivations to

leave.

In a framework

of gender relations that distributes suspicion in a generalized and class-based

way, the awareness of fault is presented and modulated through a strategic back

and forth of strength and weakness. Thus, submission or repentance coexist with

rebellious interpellations that - very carefully - evidence the contradictions

of the gender norm.

Final reflections

In this work, we set out to reflect

about the missionary efforts in the Araucanía Region, a political subject that

has been scarsely researched as a constitutive part of the history of missions,

education, and women. Specifically, we worked with the application dossiers of

young German women who, in the context of the establishment of the Third Reich

(1932-1934), applied as candidates to the newly formed congregation of

Catechist Missionaries of Boroa.

Thus, we

analyzed the calls for applications and requirements set by the Capuchins who

directed the Mission, identifying how these documents outlined the

missionaries” profile through specific requirements (money for the journey,

independence from parents, health, youth) and a subtle modulation of behaviors

and “correct feelings” (character, humility, sacrifice, vocation). We concluded

that these documents displayed proposals of identification for the candidates

which involved everything from the “paradisiacal landscape” of southern Chile

to a feminine epic that articulated the domestic ideal with the discourse of

female moral superiority.

On the other

hand, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the documents written in the first

person by the candidates (autobiographies, letters). This allowed us to

identify both exceptionalism and the tricks of the weak as two paradoxical

strategies that sought to respond to the expectations of the “missionary”

profile and its implicit promises of recognition, autonomy, and mobility.

These Catholic,

rural German women, impoverished amidst a severe sociopolitical crisis, encoded

various presentations of themselves that included desires, silences, masks,

ambivalences, and rebellions with the strategic aim of shielding themselves

from suspicion and having an opportunity to start a new life.

We therefore

conclude that exceptionalism and the tricks of the weak were responsible, on

the one hand, for presenting strength (both physical and of character), youth,

courage, and a vocation for sacrifice as guarantees of the candidates” triumph

over their own flesh, a matter that would invest their cultural and racial

hierarchy with the pagans. On the other hand, in parallel with this

demonstration of strength, the candidates outlined a series of simulations of

innocence, harmlessness, and submission that - in their attempt to avoid

possible conflicts with the priests - confirmed the gender binary and

hierarchy: childish and suspicious femininity versus rational and

self-controlled masculinity.

However, for

some candidates, this paradoxical and careful encoding between strength and

weakness achieved the feat of crossing gender boundaries. An achievement in

autonomy and recognition legitimized through a hierarchy among women. The

traces of these discursive juggling acts as ways of departing towards a new

world, run through women’s stories: stories that are never evident, and always

problematic.

Bibliography references

Archives

Historical Archive of the Diocese of Villarrica

(AHDV).

File “First candidates to the Catechists of Boroa

1932-1934”

Sister Superior Engelmann. (1932, August 19). Kempten.

AHDV.

Sister Superior Leonarda Welsh, Sisters of the Good

Shepherd. (1932, August 16). Münich. AHDV

Father Räglau. (1933, September 3). Parish of

Baden-Baden. AHDV.

Pastor K. Arnow. (1932, September 10). Reichenbach.

AHDV.

Parish office of Saarbrücken. (1932, June 21). AHDV.

Father Caedilian. (1933, June 24). Burghausen. AHDV.

Letter from Father Eduard to Guido Beck. (1932, August

12). AHDV.

Letter from Guido Beck to Father Eduard. (1932,

September 29). AHDV.

Letter from Father Eduard to “his Reverence”. (1934,

July 20). AHDV.

Lina Koch. (1933, September 10). Baden-Baden. AHDV.

Elisabeth Schneider. (1932, June 14). Saarbrücken.

AHDV.

Maria Renninger. (1933, June 28). Mabmberg. AHDV.

Gisela Eckstein. (1933, June 14). Mammersreuth. AHDV.

Father Johannes. (1932, August 23). Cleve. AHDV.

Father Feuerbach. (1932, August 29). Parish office of

Mainz. AHDV.

Letter from Father Eduard to ‘His Excellency’. (1933,

May 4). Altötting. AHDV.

Letter from Father Eduard to Guido Beck. (1934, August

20). AHDV.

Father Suitbertus to Father Eduard. (1933, September

28). Mainz. AHDV.

Letter from Klara Mergler to ‘His Excellency’. (1934,

August 5). Gernsheim. AHDV.

Margareta Maier. (1934, July 29). Bamberg. AHDV.

Maria Renninger. (1933, June 28). Mabmberg. AHDV.

Franziska Schmid. (1932, December 29). Öettingen.

AHDV.

Ottilie Winter Maier. (1934, September 14).

Untermühlbach. AHDV.

Archive of the Mother House of the Catechist Sisters

of Boroa (ACB).

“Date of birth

and religious profession of the missionary catechist sisters”. (n.d.). ACB.

Ewige Anbetung and Altöttinger Franziskus Kalender magazines,

Library of the university of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Bibliographic

Ahmed,

S. (2017). La política afectiva del miedo. In La política cultural de las

emociones (pp. 105-132). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Azócar,

A. (2014). Así son… así somos. Discurso fotográfico de capuchinos y

salesianos en la Araucanía y la Patagonia. Ediciones Universidad de la

Frontera.

De

la Fuente, P. (2023). Ñimin y escritura: encuentros y desencuentros entre

niñas y mujeres mapuche con misioneras anglicanas en la Misión araucana de SAMS

(1895-1929) Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago.

Donoso,

A. (2008). Educación y nación al sur de la frontera: organizaciones mapuche

en el umbral de nuestra contemporaneidad, 1880-1930. Pehuén, RIL.

Dorlin, E. (2003). Les putes sont des hommes comme les

autres. Raisons Politiques, 3(11), 117-132.

Egaña,

L.; Nuñez, I. & Salinas, C. (2003). La educación primaria en Chile,

1860-1930 :

una aventura de niñas y maestras. LOM.

Haggis, J. (1998). ’A heart that has felt the love of

god and longs for others to know it’: conventions of gender, tensions of self

and constructions of difference in offering to be a lady missionary. Women’s

History Review, 7(2), 171-193.

Illanes,

M. (2007). Cuerpo y sangre de la política La construcción histórica de las

visitadoras sociales (1887-1940). LOM.

Lavrin, A. (1995). Women, Feminism and Social

Change in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay 1890-1940. University

of Nebraska Press.

Ludmer,

J. (1985). Tretas del débil. In P. González & E. Ortega (Eds.), La

sartén por el mango. Encuentro de escritoras latinoamericanas (pp. 47-54).

Ediciones El Huracán.

McClintock,

A. (1993). Family feuds:

gender, nationalism and the family. Feminist Review,

44, 61-80.

Menard,

A. & Pavez, J. (2007). Mapuches y anglicanos. Vestigios fotográficos de

la Misión Araucana de Kepe, 1896-1908. Ocho libros.

Montecino,

S. & Foerster, R. (1988). Organizaciones, Lideres y Contiendas Mapuches

(1900-1970). CEM.

Noggler,

A. (1972). Cuatrocientos años de Misión entre los Araucanos. Editorial

San Francisco.

Riot-Sarcey,

M. & Varikas, E. (1988). Réflexions sur la notion d’exceptionnalité. Les

Cahiers Du GRIF, 37-38, 77-89.

Rivière,

J. (1929). Womanliness as a mascarade. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, X, 303-313.

Rojo,

G. (2001). Diez tesis sobre la crítica. LOM.

Rosa, E. (1996). Sor Juana and Gabriela Mistral:

Locations and Locutions of the Saintly Woman. Chasqui, 25(2),

89-103.

Semple, R. (2003). Missionary women : gender,

professionalism, and the Victorian idea of Christian mission. Boydell

Press.

Scott,

J. (2012). Las mujeres y los derechos del hombre :

feminismo y sufragio en Francia, 1789-1944. Siglo Veintiuno

Editores.

Serrano,

S. (1995). De escuelas indígenas sin pueblos a pueblos sin escuelas indígenas:

la educación en la Araucanía en el siglo XIX. Historia, 29,

423-474.

Serrano,

S., Ponce de León, M., & Rengifo, F. (2018). Historia de la Educación en

Chile, Tomo II: La Educación nacional (1880-1930). Taurus.

Stoler, A. (2004). Affective States. In D. Nugent

& J. Vincent (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics

(pp. 4-20). Blackwell Publishing.

Stornig, K. (2013). Sisters Crossing Boundaries:

German Missionary Nuns in Colonial Togo and New Guinea, 1897-1960.

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Umbach, J. (2017). Missionarische Weiblichkeit und

Identitätskonstruktion. Die Chile-Mission der Menzinger Kreuzschwestern im

frühen 20. Jahrhundert. Peter Lang Edition.

Vera,

A. (2016). La superioridad moral de la mujer: sobre la norma racializada de la

femineidad en Chile. Historia y Política, 36, 211-240.

Vera,

A. & Sáez, C. (2022). Animales monstruosos y viriles: una lectura feminista

del archivo de la repugnancia a las cobradoras de tranvía (Santiago, fines

XIX-comienzos XX). Cadernos Pagu, 65. https://www.scielo.br/j/cpa/a/QYVzC7rJ7gf347cYd4zYL6k/

Vera,

A. & Valderrama-Cayumán, A. (2017). Teología feminista en Chile: actores,

prácticas, discursos políticos. Cadernos Pagu, 50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201700500012

Yeager, G. (2005). Religion, Gender Ideology, and the

Training of Female Public Elementary School Teachers in Nineteenth Century

Chile. The Americas, 62(2), 209-243.

Yuval-Davis, N. & Anthias, F. (1989). Women-Nation-State.

Macmillan.

Antonieta Vera Gajardo

Chilean. Has a PhD in Political

Science with specialization in Gender Studies, Université Paris VIII. Professor

of the Department of Philosophy-Center for Gender and Cultural Studies in Latin

America, University of Chile. Lines of research: Feminist Political Philosophy

and Gender Studies, Strategies and Politics of Difference, Intersectionality,

Discourse Analysis and Postcolonial Feminist Theory. Recent

publications: “Champurrias, awinkadas y warriaches: interpelaciones al

‘mapuchómetro’ desde las coves de mujeres mapuche contemporáneas en regiones

Metropolitana y Araucanía” (2024) and Aguilera, Isabel; Vera, Antonieta &

Fernández, Rosario (2023) ‘Un estallido animal: Animalización y

antropomorfización en el conflicto político chileno’.

Camila

Stipo

Chilean.

Master’s in philosophy, University of Chile. Professor at the University of

Santiago. Research interests: feminist political philosophy, feminist

posthumanist theory, sustainability and water crisis. Recent publications: “Feminismo posthumanista y

crisis hídrica en la obra Kowkülen de la Seba Calfuqueo” (2024) and “Vivir y

pensar con otras: La experiencia de un violador en tu camino. Los espectros de

la dictadura a medio siglo del golpe” (2024).

Rosario

Fernández

Chilean. Has a PhD in Sociology at

Goldsmiths-University of London. Professor at the Faculty of Philosophy and

Humanities, University of Chile. Lines of research: feminist philosophy and

gender studies; affects and emotions; power; dance and movement. Recent

publications: Fernández, Rosario and Chan, Carol (2024) “We are not equal”:

Beyond shared desires for horizontality and disillusionment in relationships

between employers and internal and international migrant domestic workers in

Chile and Julieta Kirkwood in Colección Cuadernos Pensadoras Feministas

Latinoamericanas (2023).