|

OSCAR GERARDO Universidad Autónoma BENJAMIN TONEY University of Southern California Recibido

|

Museums as social and cultural spaces for active

ageing: evidence, challenges, and opportunities Abstract: The work addresses access to Museums as cultural spaces by older

adults in Mexico. The access, use, and knowledge they have regarding museums

are analyzed. The analysis is carried out by rural or urban origin, travel

time, gender, education levels, among other variables. The database used is

the Museum Statistics for 2017 published by INEGI in 2018 and the method used

consisted of crossing variables. The National Statistical Directory of

Economic Units database was accessed to cross-check statistical information

with georeferenced points of museums throughout the country. The work adds

two different dimensions of study, 1) to the studies of aging and old age,

when verifying the mobility, cultural interests and social connectivity of

the elderly and, 2) to the studies on museums and cultural spaces, by

demonstrating the persistence of access and interest on the part of older

adults. Keywords:

Museums; Elderly; Social Connectedness; México; access to cultural

spaces.

Los museos como espacios

sociales y culturales para el envejecimiento activo: evidencia, desafíos y

oportunidades Resumen: Este trabajo aborda el acceso de adultos

mayores de México a los museos como espacios culturales. Se analiza el

acceso, uso y conocimiento que tienen respecto a ellos. El análisis se

realiza bajo las siguientes variables: origen rural o urbano, tiempo de traslado,

género, nivel educativo, entre otras. La base de datos utilizada es las

Estadísticas de Museos del año 2017 (INEGI) y se usó el método de cruce de

variables. Se accedió a la base de datos Directorio Estadístico Nacional de

Unidades Económicas para cruzar información estadística con los puntos

georreferenciados de museos en todo el país. El trabajo agrega dos

dimensiones de estudio diferentes, 1) a los estudios del envejecimiento y

vejez, al comprobar la movilidad, intereses culturales y la conectividad

social de los adultos mayores y, 2) a los estudios sobre museos y espacios

culturales, al demostrar la persistencia del acceso e interés de los adultos

mayores. Palabras

clave:

Museos; personas

adultas mayores; vinculación social; México; acceso a espacios culturales.

Cómo citar Hernández, O. y Toney B. (2021). Museums as social

and cultural spaces for active ageing. Evidence, challenges, and

opportunities.

Culturales,

9, e588. https://doi.org/10.22234/recu.20210901.e588 |

Introduction. The context of the new wine geographies

Roughly 10% of the

population of Mexico is over the age of sixty – and the gross number can be

expected to continue to increase as age cohorts age. This demographic group

increased from 3.5% to 10.4% of the total population between 1900 and 2015 when

they reached 12 million, a momentous demographic shift in age distribution. The

ageing index – the number of older adults -people 60 years and older- per 100

children – grew from 16 in 1990 to 21 in 2000 and has reached 31 in 2015. The

median age has grown from 19 in 1950 to 23 in 2000 and 27 in 2015 (INEGI,

2015). Mexico City is the oldest state with a median age of 33, while Chiapas

is the youngest with median age 23. Mexico’s demographic shift is widely

studied for its expected consequences and future challenges (Ham, 1999; Partida, 2005). As more people are living longer lives,

there are accompanying social, institutional, and cultural shifts that are

needed to ensure that older inhabitants of Mexico can survive and thrive.

One

component of great importance to that ability concerns access to cultural

spaces for the recreational, educational, and social benefits that these spaces

can support. As such, museums have the potential to play an important role in

supporting the ageing needs of elders. We analyze 2017 data from the Museum

Statistics database published and managed by the National Institute of

Statistics and Geography of Mexico (INEGI). The database consists of data

collected by museum personnel during visits as well as characteristics about

Museum Institutions. The data show how older adults can make use of museums

relative to younger adults, and in turn, raises important questions for

designing programs and institutions that effectively support Active Ageing.

Active Ageing is a

timely framework for the reasons previously mentioned. While populations

globally are ageing due to progress in healthcare and food access, many

societies are now faced with larger elderly populations with distinct social

and cultural needs. In this paper, we seek to characterize museum access and

use patterns by elderly adults at the national level and compare those to

patterns of younger adults. We also disaggregate some elderly use patterns

across gender (reported in the survey as a binary variable between male and

female). We hypothesize that aged 60+ elderly adults’ use of museums often

differs from the use by younger adults between the ages 18-59. On social

dimension variables, we expected older adults to be less likely to have

received family stimulus for cultural consumption, more likely to be first time

visitors, more likely to visit alone (related to social isolation), and likely

to be less educated than their younger adult peers.

On access dimension

variables, we expect a higher reliance on public transit use and walking by

younger adults, greater times traveled by older adults, and lower rates of

participation by older rural adults compared to younger rural adults due to a

combination of transportation access and bodily ability differences among older

residents. For the purposes of this paper, we will not be able to definitively

explain the reasons behind the differences observed, but we can suggest

possible explanations and avenues for further research. Based on the patterns

observed, Museum Institutions may consider specialized programs and service

considerations to support active ageing functions to attract older patrons and

create spaces that older adults can use to increase their active aging and

social connectedness. Table 1 shows hypotheses based on the variables we

studied, grouped according to the Active Ageing framework proposed by the World

Health Organization (2002).

Table

1. Hypothesizing based on Active Ageing dimensions.

|

Active

Ageing Dimension |

Hypothesis |

||

|

Survey

Variable |

Younger

Adults |

Elders |

|

|

Social |

Family

Stimulus |

More

Likely |

Less

Likely |

|

|

1st Visit |

Less

Likely |

More

Likely |

|

|

Visit

Alone |

Less

Likely |

More

Likely |

|

Personal |

Reason

for Visit |

Learning |

Accompaniment |

|

|

High Education

Level |

More

Likely |

Less

Likely |

|

|

Method of

Discovery |

Family/Internet |

Relational |

|

|

Use of

Services |

Exhibit |

Exhibit |

|

|

Reported

Learning |

Likely

Higher |

Likely

Lower |

|

Physical |

Rural

Visitors |

Likely

Higher |

Likely

Lower |

|

|

Time

Travelled |

Likely Lower |

Likely

Higher |

|

|

Visit

Duration |

Likely

Higher |

Likely

Lower |

|

|

Mode of

Transit |

More

Transit |

More Auto |

Source: based on WHO

(2002)

Literature Review

Active ageing, as a

novel and prominent paradigm within ageing studies, offers various analytical

approaches (WHO, 2002; Walker, 2009; ILC, 2015; Ramos et al., 2016;

Salazar-Barajas et al., 2017), but generally centers the perspective

that ageing is a positive and important part of life, contrary to past studies

and approaches in which ageing is more associated with death and deterioration

(Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2013). “Active Ageing” is defined by the

World Health Organization (WHO) as “the process of optimizing opportunities for

health, lifelong learning, participation, and security to enhance the quality

of life as people age” (WHO, 2002: 12). To further specify, optimizing health

includes physical health status, mental health, and social connectedness. Some

results suggest that interventions on social isolation could improve structural

social support, functional social support, loneliness, and mental and physical

health (Dickens et al., 2011). In its 2002 report, Active Ageing. A

Policy Framework, the World Health Organization (WHO) makes clear that

“active” refers to “continuing participation in social, economic, cultural,

spiritual and civic affairs, not just the ability to be physically active or to

participate in the labor force” (2002: 12). The WHO policy framework focuses on

six components for active ageing: Behavioral Determinants, Health and Social

Services, Economic Determinants, Social Determinants, Physical Environment, and

Personal Determinants. Some of those determinants are related to systems and

services that might be offered to the elderly by the state or by market actors.

Others connect more closely to elders’ practices or their backgrounds.

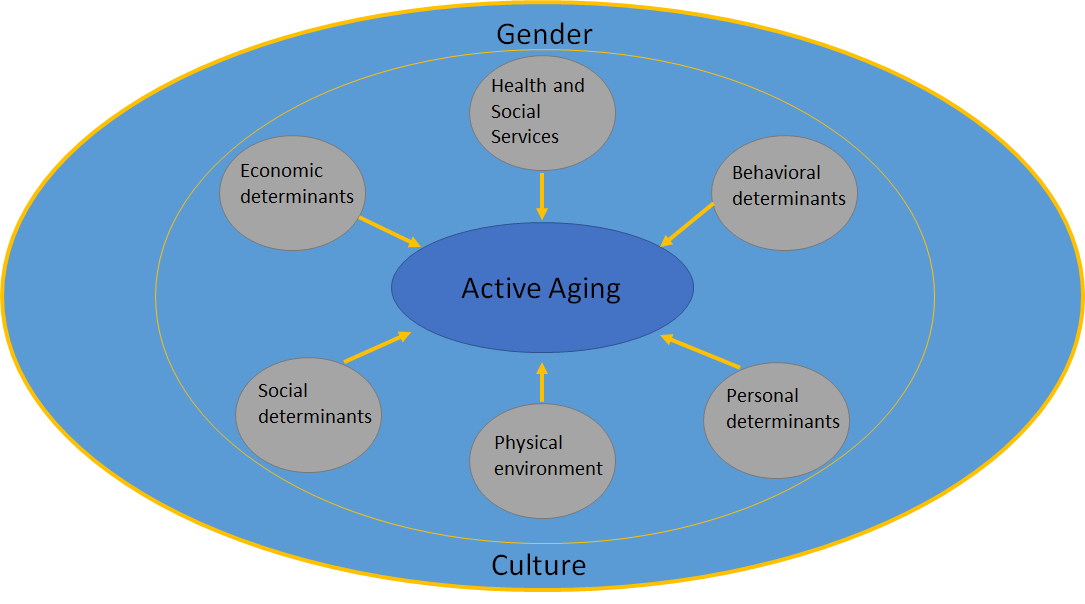

Figure 1. Active ageing. Determinants.

Source:WHO, 2002.

We

highlight three determinants of the Active Ageing framework for our purposes,

as seen in Figure 1. The first concerns Social Determinants, which focus

on preventing loneliness, social isolation, illiteracy, and lack of education,

all of which are related to older people’s risk of disabilities and early death

(WHO, 2002: 28). Various studies have demonstrated that social support and

connectedness prevent stress and can reduce the rate of decline of physical and

mental well-being (House et al., 1988; WHO, 2002, ILC, 2015). Rowe and

Kahn (1998) have concluded that social integration is a key factor to

successful ageing (Rowe & Kahn, 1998). Belonging to a group that

shares interests and activities, volunteering, strong intergenerational

relations, long-time friendship (former workmates, schoolmates, or neighbors)

shapes not only social networks for elderly people but also influence their

abilities to stay informed and connected in a society that is becoming more and

more digitally driven (Gonzalez-Oñate et al.,

2015; Jung & Sundar, 2016).

Though

ageing is associated with social isolation, elders use various strategies to

maintain social connections and build new relationships. In response to

sedentary and less mobile lifestyles in older age, going to a museum can be a

means to avoid reduced physical activity and its consequences (Palmer et al.,

2019). Leisure time and social activities can decrease isolation - leading to

depression, cognitive impairment, and mortality (Lubben,

2017). Indeed, there is a scholarship that characterizes museums as a social

experience (Coffee, 2007). Access to knowledge of their social space,

including leisure activities, also is key to active ageing and social

connectedness (Sinclair & Grieve, 2017; Cardozo et al., 2017).

According to literature (González-Oñate, et al.,

2015; Sinclair & Grieve, 2017; Yu et al., 2018), older adults use of

the internet, including Social Network Sites (SNS), is increasing, which could

serve as a way elders discover museums and other social engagement options. Also, studies on SNS have shown

that these technologies can improve their quality of life by reducing social

isolation while promoting and nurturing their social ties and new relationships

(Mo et al., 2018), and also improving their access to social benefits (Yu et

al., 2018).

The second

determinant group we use is Personal Determinants. Literature evaluating museum

use demonstrates that elderly visitors are generally interested in visiting

museums (Rogers 1998, Tufts & Milne 1999). Prior knowledge (Antón, Camarero, & Garrido, 2018) and post-visit activity

(Antón, Camarero, & Garrido, 2019) have been

linked to satisfactory experiences among visitors in general. Affect, and

emotion have also been widely understood to be important factors in shaping

museum use and satisfaction (Del Chiappa, Andreu,

& Gallarza, 2014). Fewer studies specifically

focus on elder patrons as units of study. Elottol

& Bauhaudin (2011) studied the perception and

satisfaction of elderly museum patrons in Malaysia. They find that satisfaction

among elderly patrons is related to interior pathway design and circulation

accessibility (Elottol & Bauhaudin,

2011: 277). Retcho (2017) studied elderly visitors

with and without dementia as a part of the Meet Me at MoMa

program which, specifically targeted elders with early-stage Alzheimer’s

disease; findings included some evidence of a positive effect on reported

affect, an important factor in active ageing.

The

third determinant of focus is the Physical Environment. Age-friendly

environments have been noted to be key in supporting active ageing (Pregazzi, 2017; Zamorano et

al., 2012; Sánchez y Cortés, 2016). Studies from

gerontological planning of the physical and social environment perspective

suggest that there is still a lot to do regarding spatial mobility for older

adults in Latin America (Salas & Sánchez, 2014; Sánchez y Cortés, 2016).

Pioneers of ageing studies in Mexico warned about the lack of readiness of

certain urban systems facing the ageing process (Welti,

2001; Serrano et al., 2009). Nowadays, diverse research focuses on

analyzing and preparing cities and programs to offer friendly and accessible

spaces for older adults (Pregazzi, 2017; Zamorano et

al., 2012). Recent studies focus on human rights for the elderly (Huenchuan & Rodríguez-Piñeiro,

2010; Rodriguez et al., 2018) and also on their autonomy, mobility, and

adaptation (Hernandez, 2018). With respect to museums, the number of museums

and their spatial distribution likely impacts elders’ use.

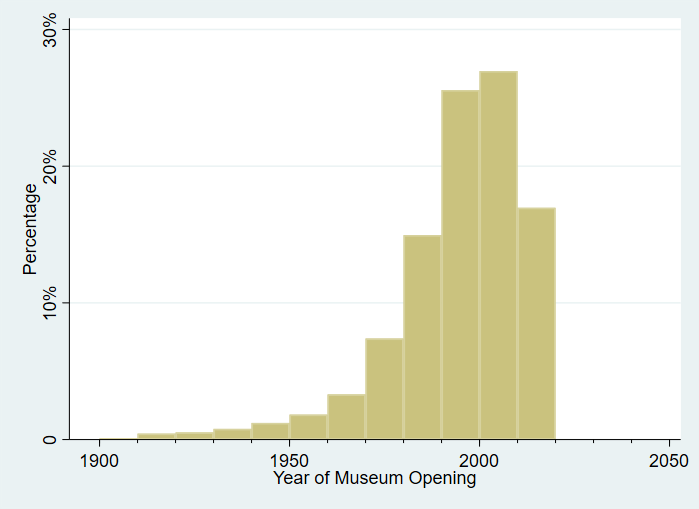

Graph

1 illustrates the temporal pattern of Mexican Museum openings since the

beginning of the 20th century. Over 90% of the museums cataloged in the DENUE[1] database opened in 1970 or later. Museums

became more involved in economic, political, and social issues from the 1970s

(Prince, 1990). This was because culture took on a more central role within the

social consciousness that connected territory, museums, and society (Gilabert & Lorente, 2016)

through a “dialectic interrelation between culture, identity and heritage”

(Alonso, 1993; cited in Gilabert and Lorente, 2016: 58). We consider this an important

pre-condition for elders to rely on museums to express and satisfy social and

cultural interests over time.

Graph 1. Evolution of museums openings in México.

Source: INEGI, 2018

The

1970s represented a shift in museum policy marked by the decentralization of

cultural institutions in México. This shift included an increased focus on

“grassroots cultural activities, [as] the celebration of the cultural heritage

of the indigenous, the rural, and the popular sector, became one of the central

topics of cultural policy since the 1970’s” (Komatsu, 2003: 2). The geography

of museum locations has dispersed in concert with the expansion in numbers both

in rural and urban areas, which is relevant to residential proximity and

transportation access today.

By

doing so, museums began to connect collections and topics with the context and

social environment where they locate (Romero de Tejada y Picatoste,

2002; cited in Gilabert and Lorente,

2016: 86). During this period, the number of museums skyrocketed due to growing

publicly funded museums, private art collections made available to the public,

and community museums.

It is

important to note that a variety of museums may include variations on how

individual institutions are run. Shieldhouse (2011),

for example, demonstrates how the role of institutional planning and

implementation can affect the number of visitors and the quality of visits for

UNESCO World Heritage sites in Mexico.

The

degree to which museum operation in Mexico specifically targets the

accommodation of elderly patrons likely varies across institutions and may be a

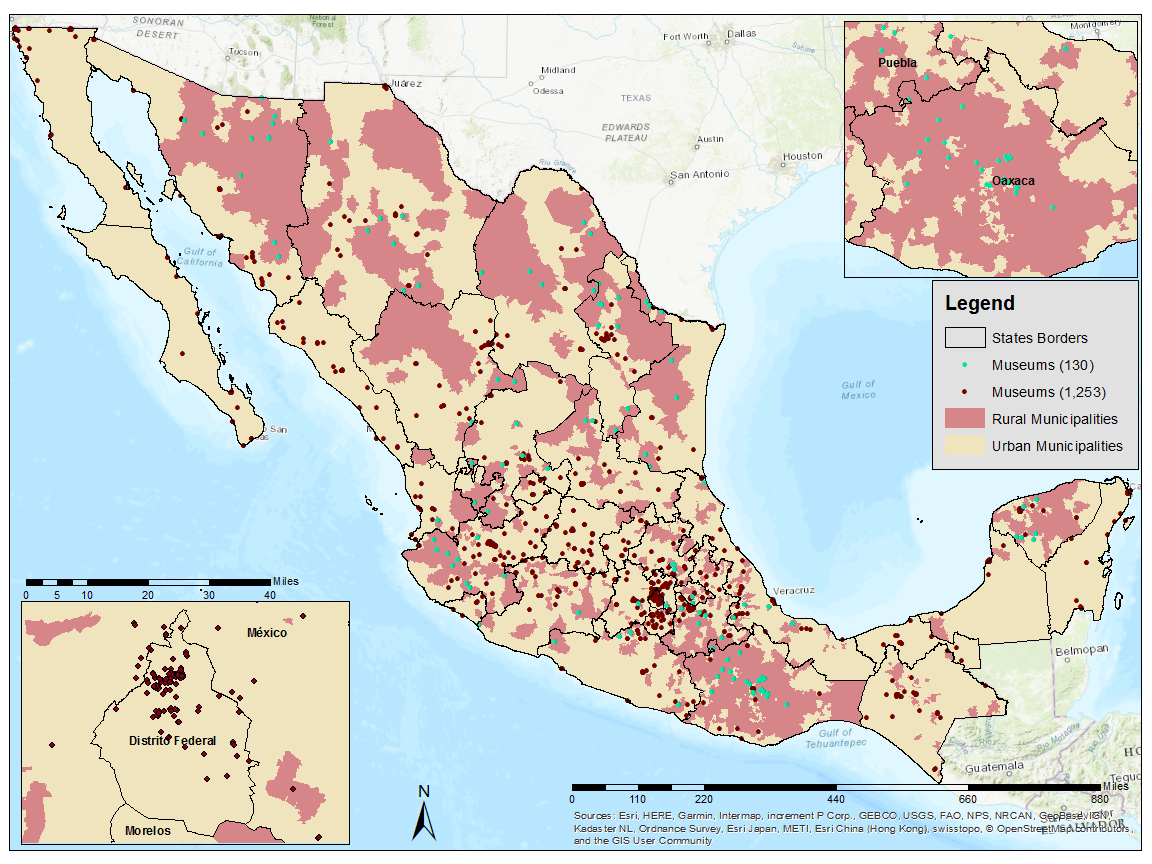

useful avenue for future research. Map 1 (using geolocation data from DENUE)

and Table 2 (using museum municipality data and urban/rural status by

population from INEGI) show patterns of museum location nationwide.

Table 2.

Location of museums by rural or urban. México.

|

Museum

Location |

Urban Municipality |

Rural Municipality |

||

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

Mexico |

1,126 |

89.8 |

130 |

10.1 |

Source: INEGI, 2018.

Map 1. Museums by rural and urban location.

México.

Source: INEGI, 2010 (Geostatistic)

and 2019 (DENUE).

Existing

literature on transportation mode choices does not yet expansively cover

patterns in Mexico, and much less research is explicitly dedicated for trips to

cultural recreation destinations among elderly residents. Guerra (2014)

demonstrates that in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area, the relationship

between the built environment and Vehicle Kilometers Travelled (VKT) among

driving households likely strengthened between 1994 and 2007, though the

relationship was not substantially different than in U.S. cities. In a study of

mode choice in the 100 largest urban areas in Mexico, Guerra et al.

found men to be less likely than women to use transit than to drive, bike, or

walk, while car use was more likely than transit use for residents up to 44

years of age than for residents older than 44 (Guerra et al., 2018:

102). Harbering and Schlüter (2020) find a similarly

gendered pattern in the Metropolitan Area of the Mexico Valley, where women are

more likely to use transit than cars, and add that higher education is

positively associated with car use. Other studies outside of Mexico (O’Fallon

and Sullivan, 2003) indicate that car usage can be expected to be higher for

leisure trips in some cases.

Lastly, we take

into consideration differences among male and female reporting respondents

among the elderly age group. Studies on the relationships between gender and

ageing have deep roots in demographic and ageing studies. Active Ageing

frameworks have frequently been applied in the Global North. Montero López et

al. (2011) find in Spain some evidence of objective and perceived health

declines to be more severe in women among a group of 456 elders (Montero López et

al., 2011: 608). Foster & Walker critique the dominant productivist frames of active aging in the European Union,

which “largely ignore the different needs of older men and women” (Foster &

Walker, 2013: 7), suggesting in its place a life course approach that validates

needs at different stages of life and decouples the deserving of support from

economic productivity.

Studies about

gender in old age point to several differences among men and women, this is

undoubtedly influenced by the fact that women can be disadvantaged in

comparison to men when it comes to labor, income, and educational attainment (Freixas, 1997; Muñoz & Espinosa, 2008; Fernández-Mayoralas et al., 2015). Safety is a concern that

affects both transportation and the use of public space (Yavuz & Welch,

2010). Longer life expectancy worldwide can mean that some older women spend

aged years alone (Muñoz & Espinosa, 2008). Muñoz and Espinosa highlight

that gender is “a cross-sectional determinant of active ageing and reflects

huge disadvantages of older women” (2008: 305). While this study cannot speak

to speak directly to health and socioeconomic dimensions specifically,

including gender analysis helps to understand challenges and opportunities for

policies, facilities, institutions, and academic research to support active ageing

outcomes for people of different identities who may have different needs.

To investigate

the three components of an active ageing framework on Mexican visitors to

museums, we compare adults aged 18-59 to adults 60 and overusing crosstab

analysis. To expand further, we apply a gender analysis to disaggregate older

visitors into male and female respondents to determine if gender differences

appear in elderly visit characteristics.

Data and Methodology

Studies on cultural

access and cultural consumption regarding museums in Mexico continue to grow.

During the 1980s and 1990s, research on museums and cultural access

accelerated, but still, it is short nowadays (Schmilchuk,

2012; García, 1993 & 1999; Rosas 2002 & 2007). Scholars have noted a

political dimension to using time to visit spaces conceived for leisure and

information. The use of time “constructs us as citizens, as social individuals,

it impulses or bans us to think, feel and act on reality and on ourselves” (Schmilchuk, 2000: 79). Schmilchuk (2000) advocated for a better understanding of the

experience of museum use and thus for better databases about museums and their

visitors. She emphasized the necessity of knowing more about those elements to

improve not only museums per se but visitors’ investment (in time spent

and physical effort) and visitors’ perceptions.

There

is a relatively short list of databases related to cultural access and venues

in Mexico. The most recent effort is the Estadistica

de Museos. It ran in 2016, and it is planned to

continue yearly. This database allows users to learn more about museum

institutions, access, size, and their visitors. The database has three

components – a survey of museum institutions’ characteristics, museum

institutions’ volunteership and social service

offerings, and museum visitors’ characteristics collected in interviews of

patrons by museum staff.

In

response to García’s (1993) claims about museum use data, the Estadísticas de Museos database

makes a great improvement in showing museums’ and visitors’ characteristics. We

worked with the database of the year 2017, which featured 171,627 individual

patron responses. After dropping missing data, unspecified responses, museum

visitors not from Mexico, elders above age 97 who had been grouped under a

single code, and youth aged 13-17, the final sample we used was 129,652

individuals, of which 10,419 were 60 years or older. Some key assumptions

impact our use of this data. Firstly, since patrons were interviewed by museum

staff, it is possible that patrons willing to spend additional time to

participate were predisposed to report more favorable outcomes.

There

are also general assumptions about precision and accuracy in self reporting on

variables like travel time. The survey also does not ask if the travel was

specifically to visit a museum or if visiting one was added as part of a larger

trip. Other limitations from this database include a lack of information about

visitor’s socioeconomic status and travel distance. However, municipality of origin

and travel time help illustrate where older and younger adult patrons come from

and how long they are willing to travel.

Further,

the structure of data for some responses required some manipulation. For

example, educational attainment data

was reported across two variables – the highest level of education reached and

whether that level was completed. To group individuals by educational

attainment, we assigned individuals to the highest level completed. In

addition, because levels of education were spread across 9 categories (ninguna, Primaria, Secundaria, Estudios técnicos con secundaria terminada, Normal básica, Preparatoria o bachillerato, Estudios técnicos con preparatoria terminada, Licenciatura, Maestría o doctorado), we

collapsed those levels into 5 categories (none, Less than High School, High

School, Bachelor’s Degree, Master’s Degree or Higher).

In addition,

respondents answered yes or no to a series of questions regarding whom they

visited and their motivations to visit, and each respondent has the ability to

select multiple responses. We present the percentage of respondents who

reported a given motivation or type of companion to compare these variables.

Findings

Social and Personal Dimensions of Museum

Use

In the context of active

ageing (WHO, 2002; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2013; Rowe & Kahn

2015; Fernández-Mayoralas et al., 2015, ILC,

2015), social activity and connectedness are vital for health and daily life

issues for the elderly. Likewise, the continuous search for knowledge and

satisfaction of curiosity is an important element in active and successful

ageing. We investigated social dimensions of museum use with the following

questions: with whom do older adults go to museums? What motivates them to go

to a museum? Is it to accompany somebody or for personal reasons and interests?

Do they have established preferences to visit museums? By what means do older

adults find out about the existence of museums or exhibitions?

In

addition to their role as places of history, knowledge, and memory (Sandell, 2003), museums also serve as points for meetings,

for social, academic, and cultural activities (Camic

& Chatterjee, 2013; Antunes & Jesus, 2018). To investigate a social

dimension of visitors’ cultural background, we analyzed if respondents received

family stimulus for cultural consumption during their childhood. Among all

respondents, 85,077 (65.6%) said they received family stimulus for cultural

consumption during childhood. Of that group, 4,911 were age 60 or older,

representing about 47% of the sample’s total 10,419 persons aged 60 or over.

The younger adult groups received family stimulus much more frequently at about

67% of the time.

Table 3. Family Stimulus and First Visit to a

museum. México.

|

Received Family Stimulus for Cultural Consumption |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

80,166 |

67% |

4,911 |

47% |

|

No |

39,067 |

33% |

5,508 |

53% |

|

First Time Ever Visiting a Museum |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

81,562 |

68% |

6,676 |

64% |

|

No |

37,671 |

32% |

3,743 |

36% |

Source:

INEGI, 2018.

We

also analyzed if the visit they were surveyed was their very first visit to any

museum. Table 3 shows reported first visits for 68% (81,562) and 64% (6,676) of

the younger adult and elderly adult respondents, respectively. This finding was

inconsistent with our expectations, though the proportion of first-time

visitors was similar among the age groups we constructed. The proportion of

elders visiting for the first time might decline over time as younger cohorts

that have already visited a museum age into their elder years; until then,

programming implications include engaging first-time visitors across age

groups.

To

examine how visitors’ preexisting social relationships shaped visits, we

analyzed companions during visits. 1,494 (14%) of older adults went alone,

while 8,925 went with someone. This suggests that elders are able to use

museums to engage as individuals as well as to reproduce existing relationships.

The most common companions for the elderly were relatives, with 55% (5,716),

friends (14% or 1,461 individuals), followed by partners (11% or 1,190

individuals).

The

expectation was to see a higher share for tourist companions, but it only appeared

for 5% of the elderly respondents. As expected in comparison to younger adults,

elders seldom visited with companions related to school or work. Data regarding

companions for the young and old groups can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. Accompaniment by Age Group. México.

|

Nobody |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

14,162 |

12% |

1,494 |

14% |

|

No |

105,071 |

88% |

8,925 |

86% |

|

Relative |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

57,544 |

48% |

5,716 |

55% |

|

No |

61,689 |

52% |

4,703 |

45% |

|

Romantic Partner |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

16,996 |

14% |

1,190 |

11% |

|

No |

102,237 |

86% |

9,229 |

89% |

|

Friend |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

23,348 |

20% |

1,461 |

14% |

|

No |

95,885 |

80% |

8,958 |

86% |

|

Coworker |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

2,827 |

2% |

213 |

2% |

|

No |

116406 |

98% |

10,206 |

98% |

|

Schoolmate |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

6,411 |

5% |

106 |

1% |

|

No |

112,822 |

95% |

10,313 |

99% |

|

Tourist Group |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

Yes |

1,640 |

1% |

572 |

5% |

|

No |

117,593 |

99% |

9,847 |

95% |

Source: INEGI, 2018.

Huijg and

colleagues (2017) define Plans and Wishes

as important factors during old age. The top three motivations elderly visitors

reported for their visit were for general cultural engagement (51%), to learn

something (31%), and finally, to accompany somebody (26%). For the younger

adults, the same top three motivations were reported at the following rates:

cultural engagement (45%), learning (31%), and accompanying another (25%). For

the elderly, cultural motivations were higher than the population average. This

pattern was surprising since fewer of them received family stimulus-suggesting

that the impetus for cultural engagement comes from multiple sources. These

reports from visitors demonstrate the intent to use museums for precisely the

types of activities that support active ageing. Some research has found that

the elderly see museums as options to be active, engaged, and healthy (Hovi‐assad, 2016; Huijg et al.,

2017) since it is an activity that makes them go out move and

interact with their surroundings.

Educational

background is another important dimension of active ageing. Table 5 shows the education levels of visitors

compared to nationwide averages by age groups. We find that, contrary to

expectations, elderly visitors are, in fact, more likely to have higher

educations than the younger adult visitors in addition to having higher

educations than the population at large. Such a pattern could be the result of

self-selection where education level relates to an interest in visiting, the

result of barriers to entry where education level relates to sociospatial advantage and facilitates easier access for

the educated, or a combination of the two. However, elderly visitor populations

had proportionally larger groups with little to no education. This would be

consistent with the finding that many elderly visitors report learning (31%) as

a motivation to visit –older adults with lower educational attainment may see

museums as an opportunity for continued learning. Regardless, it is clear that

the universe of visitors we studied is not representative of the larger

population on educational attainment, a pattern relevant for institutions

prioritizing inclusion among diverse elder populations.

Table 5.

Educational levels. Estadística de museos sample vs. Nationwide averages. México.

|

Education

Level |

Population (18-97) |

Visitor (18-97) |

Visitor (18-59) |

Visitor (60-97) |

|

(N =

55,036,609) |

(N= 129,652) |

(N =

119,233) |

(N= 10,419) |

|

|

None |

10% |

0% |

0% |

2% |

|

Less than

High School |

49% |

22% |

21% |

34% |

|

High

School |

20% |

37% |

39% |

20% |

|

Bachelor's |

3% |

34% |

34% |

33% |

|

Master's

or Higher |

2% |

7% |

7% |

11% |

Source: INEGI, 2018.

We

also investigated the method of discovery among different visitors. Literature

refers to the importance of prior knowledge to the experience of museum

visitors, and thus how individuals find out about exhibits/museums may

influence the active ageing potential of museums. Older visitors reported

social relationships like friends and family (32.3%), past knowledge of the

museum (22%), followed by Offices of Touristic Information (11%) were the top

three ways they encountered the museums. Younger visitors reported slight

differences, learning of the museums by friends and family relatives (31%),

teachers (15%), and past knowledge of the museum (15%). Internet use was low

among both groups, though lower as expected among the older visitor group. Only

3% of older adults said they used SNS, and only 6.2% used the Internet to know

about the museum. We also explored whether the visit to a museum was planned or

not, considering that planning activities can be important to maintaining

physical and mental well-being for elders (Huijg et

al., 2017). We found out that 52% of the overall visitors did plan their

visit. Rates were similar among the older adult groups (54% or 5,642) and the

younger adult groups (52% or 62,090) in planning visits prior to attending

museums. Older adults planned slightly more frequently, but overall large

portions of both groups chose to visit more spontaneously, an ability likely

influenced by the freedom of time, spatial proximity, and transportation

access.

How a

museum is used helps to understand its potential as a site for active ageing;

thus, we explored use patterns. The use of services followed similar patterns

among age groups. The top three services were the exhibitions (91.5%), guided

visits (30.4%), and the stores/gift shops (17.3%), which each had similar

response rates among older and younger adults alike. None of the other services

polled in the survey, were used by more than 6% of the sample. Service use can

partly be explained by service provision, which was measured from the museum

characteristics database (N=1,256).

With

respect to the two most commonly used services, 96.5% of museums featured

exhibitions, and 83.7% featured guided visits. However, there were cases where

commonly provided services were seldom used. 44% of museums offered arts and

cultural activities, while only 5.1% of survey respondents reported using them.

Meanwhile, there were also cases where use was sizable despite less frequent

provision. Though only 27.0% of museums reported stores or gift shops, 17.3% of

patrons still reported using them. This is consistent with former studies,

including Rogers (1998), which demonstrated how gift shops have become

increasingly important to balance the books in museum contexts in which funding

becomes precarious. Of note is the gap between the rate of provision of ability

devices to support physical ability (14%) and the rate of use by visitors

(0.4%). It may be the case that individuals with less physical ability face

transportation challenges in reaching museums or may bring their own devices

and therefore lack the need for temporary options. However, greater support

inside and outside museums is likely needed to ensure active ageing can occur

despite ability differences.

As

part of the social determinants involved in active ageing, nurture of education

keeps elders socially connected and active within society. This gives them

tools to keep their knowledge updated and avoid social isolation and the

consequences that come with it. Curiosity has many places and times for satisfaction,

and certainly, museums are locations where elders can nurture their knowledge

and curiosity. Our analysis showed that 61% (1,973 of 3,225) of elders

whose motivation to go to a museum was “Learn” reported the highest learning

score of 10, while 58% of those who did not report learning as a motivation

reported a learning score of 10 (4,142 of 7,194). Overall, compared with

younger adults (53%), a higher share of elderly visitors (60.5%) reported the

highest level of learning. Regardless of age group, or whether learning was an

explicit goal, most visitors report having learned something new after visiting.

In this way, elders and other adults are able to use museums for lifelong

learning as consistent with existing literature (Hsieh, 2010; Camic & Chatterjee, 2013; Galvanese

et al., 2014).

Physical Determinants:

Mobility, Time, Space

The spatial pattern of museums

demonstrates some dispersal of institutions with notable clustering around

Mexico City and Guadalajara. In general, the vast majority of museums recorded

in the INEGI (2018) survey (roughly 90%) are located in municipalities considered

as urban (return to Table 2 and Map 1). For elder and younger adult patrons

alike, this means that living in a rural area may make it harder to access

museums based on travel. For elders living in urban residences, who may be

closer to museum locations, transportation accessibility may be an important

factor shaping their museum use. This consideration is relevant considering

that approximately half of the visitors reported visits in which the trip was

not planned.

Table 6. Urban or Rural Origin. México.

|

Visitors |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

Urban

Origin |

115,737 |

97% |

10,083 |

97% |

|

Rural

Origin |

3,827 |

3% |

322 |

3% |

Source:

INEGI, 2018.

Contrary

to our hypothesis, older rural adults did not have lower rates of museum visits

than younger rural adults (though total numbers were lower). The survey data

indicates that in 2017 very few patrons reported living in rural

municipalities, regardless of age group. Of the 129,652 patrons in the sample,

4,149 (3%) reported dwelling in a rural municipality. As seen in Table 6,

adults aged 18-59 and adults over 60 who participated in the survey separately

reported the same rate (3%) of rural dwellings (3,831 of 119,224 and 334 of

10,419, respectively).

Table 7.

Average time travel and average time of visit (minutes) by gender. México.

|

Travel and Visit Times |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

||

|

Average time traveled (min) |

Average visit duration (min) |

Average time traveled (min) |

Average visit duration (min) |

|

|

Female |

51.7 |

61.7 |

60.7 |

66.1 |

|

Male |

54.3 |

58.8 |

61.5 |

61.5 |

Source: INEGI, 2018.

Using

data collected through the survey, we analyzed travel time and time spent in

the museum (see Table 7). On

average, older adults traveled longer periods and spent more time during the

visit. There were some differences across gender, with older females visiting

longer than older males. Table 8 shows travel times in greater detail. For rural dwellers, travel time followed similar patterns

between age groups. 78% of younger adults traveled one hour or less to reach

the museum destination, while 80% of elderly patrons took trips of that length.

The

majority of younger (54%) and elderly (59%) adults traveled 30 minutes or fewer

to their museum destination, older patrons being more likely to take short

trips. This was not surprising – as older patrons could be expected to prefer

shorter trips, or possibly transportation access could be a barrier for some

elders who would otherwise require longer trips. In terms of visit duration for

patrons coming from rural residences, young and old visitors alike reported

visits of up to one hour between 78 and 79 percent of the time (see Table 8).

Table 8. Travel Times by Age group: Rural vs.

Urban. México.

|

Minutes |

Rural |

Urban |

||||||

|

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

|||||

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

0-15 |

1,094 |

29% |

104 |

31% |

27,934 |

24% |

2,671 |

26% |

|

16-30 |

959 |

25% |

93 |

28% |

35,757 |

31% |

2,855 |

28% |

|

31-45 |

470 |

12% |

37 |

11% |

15,341 |

13% |

1,170 |

12% |

|

46-60 |

457 |

12% |

34 |

10% |

13,660 |

12% |

1,197 |

12% |

|

61-75 |

56 |

1% |

8 |

2% |

1,815 |

2% |

174 |

2% |

|

76-90 |

236 |

6% |

12 |

4% |

6,979 |

6% |

547 |

5% |

|

91-120 |

237 |

6% |

13 |

4% |

5,761 |

5% |

513 |

5% |

|

121-150 |

78 |

2% |

4 |

1% |

2,189 |

2% |

216 |

2% |

|

151+ |

244 |

6% |

29 |

9% |

5,957 |

5% |

741 |

7% |

Source:

INEGI, 2018.

The

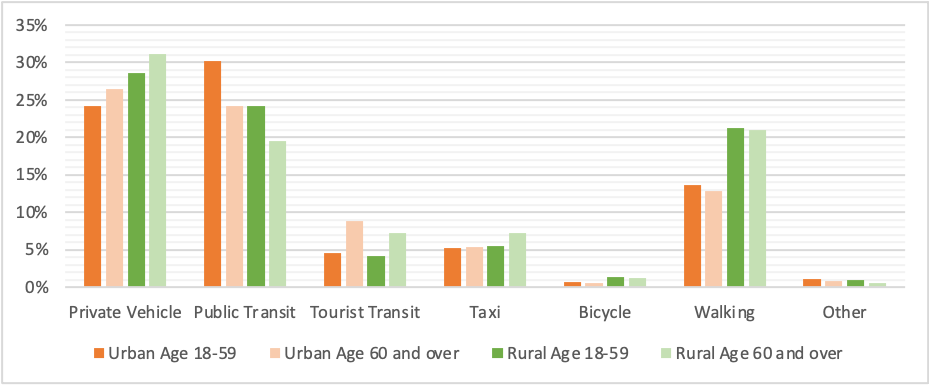

preferred mode of transportation appeared to follow a more distinct pattern by

age, however. While younger and older adults from rural areas used private

vehicles at roughly the same rates (42.55% and 43.41%, respectively) and walked

at roughly the same rates (21.22% and 20.96%, respectively), their use of other

modes varied. 24.22% of younger rural adults used public transit, while only

19.42% of older adults did the same.

The

reduced use of public transit among elderly patrons is consistent with the literature

on public transit accessibility for their age group, following that the level

of public transit services tends to be less robust in less densely populated

areas and México, public transit is not designed adequately for older adults’

use (Melgar et al., 2013; García, 2016). It is

demonstrated that the use of public transit is a gesture of autonomy. It makes

the elderly “take control of their own lives” (Attoh,

2017: 205).

Older rural adults had

higher rates of use with tourist transport (7.19% vs. 4.10%) and taxis (7.19%

vs. 5.56%) compared to rural adults of age 18-59, consistent with the

literature. However, there are various alternate potential explanations of this

travel behavior. It may be the case that the rural elder patrons who choose to

visit museums may have more disposable income on average and therefore chose

more personalized, convenient, and subsequently more expensive modes of travel.

Meanwhile, finding that about 1 in 5 rural elderly patrons walks to museums

when only about 1 out of 10 museums are in rural areas may illustrate how some

rural elders are accustomed to walking. The rural proliferation of (especially

community) museums may also have helped increase access for people in rural

places where museums are, on average sparser. For both age cohorts and rural

vs. urban, see Graph 2 and Table 9.

Graph. 2. Urban and Rural Mode of Transport by

Age. México.

Source: INEGI, 2018.

Urban

dwellers, in general, attended at much higher rates (over 96% of the sample) as

compared to rural patrons. Where rural elders were slightly more likely than

younger adults to travel one hour or less, urban elders (78%) were slightly

less likely than younger adults (80%) to take trips of that length of time. In

this case, the reversal might be explained by closer museum proximity for urban

dwelling elders. For trips 30 minutes or fewer, the urban pattern was narrower

between age groups. Where 55% of urban younger adults traveled up to 30 minutes

to visit the museum, 55% of urban older adults made trips of similar lengths.

Shorter visit durations were less common for urban museum visitors across age

groups. 72% of younger patrons and 69% of older patrons visited for one hour or

less, whereas rural visitors visited an hour or less 78% of the time.

One

could hypothesize that visitors from rural areas who spend more time in transit

spend less time in the actual museum. Urban patron visits lasted an average of

about 60.9 minutes after an average one-way trip of 53.5 minutes. Rural patrons

visited for about 52.7 minutes on average after a one-way trip of 56.5 minutes.

However, when broken down by age, we find that longer trips do not necessitate

shorter visits. The average duration for younger adults was a 52.9-minute trip

and a 60.4-minute visit. Elderly visitors traveled an average of 61.1 minutes

and visited an average of 63.9 minutes. Longer durations among elderly patrons

could have various interpretations. Longer trips could mean that elders have

spatially further residences than younger adults or that the mode of transit

simply takes longer. Visit duration could also have multiple explanations - for

example, elders might be more motivated to engage in exhibits for longer, or

their age might impact the speed at which they view exhibitions.

Mode

of transit for urban patrons demonstrated some patterns consistent and some

inconsistent with those of rural patrons. Older adults used private vehicles

slightly more frequently than younger adults, with 47.48% and 44.71%

respectively. Age groups’ likelihood of walking was comparable with older

adults walking 12.77% and younger adults walking 13.61%. Surprisingly, urban

visitors (13.54%) chose to walk less frequently than rural visitors (21.20%).

Again, elders (24.20%) were less likely to use public transit than their

younger counterparts (30.20%), though both age groups rode transit more

frequently when coming from urban origins, both findings consistent with existing

literature. While urban elders (8.84%) continued to use tourist transportation

at higher rates than younger urban adults (4.53%), there was greater parity on

taxi use among groups (5.37% and 5.21%, respectively).

Table

9. Mode of transit by rural

or urban and age cohorts. México.

|

Mode of Transit |

Rural |

Urban |

||||||

|

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

|||||

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

Private Vehicle |

1,094 |

29% |

104 |

31% |

27,934 |

24% |

2,671 |

26% |

|

Public Transit |

928 |

24% |

65 |

19% |

34,853 |

30% |

2,440 |

24% |

|

Tourist Transit |

157 |

4% |

24 |

7% |

5,227 |

5% |

891 |

9% |

|

Taxi |

213 |

6% |

24 |

7% |

6,008 |

5% |

542 |

5% |

|

Bicycle |

52 |

1% |

4 |

1% |

746 |

1% |

50 |

1% |

|

Walking |

813 |

21% |

70 |

21% |

15,703 |

14% |

1288 |

13% |

|

Other |

38 |

1% |

2 |

1% |

1,269 |

1% |

85 |

1% |

Source: INEGI,

2018.

The

use of tourist transit over public transit appears to matter for older patrons.

In all, elderly and younger patrons appeared to use museums at similar rates.

Accessibility appeared to be more related to whether a resident lived in an

urban or rural setting than whether they were above or below 60. For elders,

proximity to museums appears to be important, as evidenced by high proportions

of trips under 30 minutes and surprising proportions of rural walking visitors.

Gender

Table 10 shows gender

differences in our sample of respondents. In this age group, women were about

as likely as men to visit a museum during that year. Elderly women did spend

longer times during their visits than their male counterparts and were more

likely to plan their visits. For both groups, family members

were the most common accompaniment. According to Toepoel (2013: 366), “Partners, children, and friends can

serve as facilitators for cultural participation for the oldest.” Women

reported going with a friend more often, and men reported going alone or with a

romantic partner. Elderly women’s lower likelihood of visiting alone could have

to do with a combination of cost, access, or safety issues.

Presumably, the majority of

partnered elderly visitors were in heterosexual relationships – so the

partnership findings may reflect sampling bias in the survey process (e.g.,

talking to one partner and not the other). However, these findings point to how

elderly males and females rely on social relationships for companionship in

their museum visits. Other notable findings include a difference in the method

of discovery, where males relied on prior knowledge more often, and females

relied on social relationships and tourist offices more often. That corresponds

with the transport mode findings, which demonstrate females were more likely to

use tourist transport and public transit, while males were more likely to walk

or take a personal vehicle.

Table 10. Gender differences among elderly

attendees. México.

|

Mode of

Transit |

Rural |

Urban |

||||||

|

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

Age 18-59 |

Age 60 and over |

|||||

|

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

Private Vehicle |

1,094 |

29% |

104 |

31% |

27,934 |

24% |

2,671 |

26% |

|

Public Transit |

928 |

24% |

65 |

19% |

34,853 |

30% |

2,440 |

24% |

|

Tourist Transit |

157 |

4% |

24 |

7% |

5,227 |

5% |

891 |

9% |

|

Taxi |

213 |

6% |

24 |

7% |

6,008 |

5% |

542 |

5% |

|

Bicycle |

52 |

1% |

4 |

1% |

746 |

1% |

50 |

1% |

|

Walking |

813 |

21% |

70 |

21% |

15,703 |

14% |

1288 |

13% |

|

Other |

38 |

1% |

2 |

1% |

1,269 |

1% |

85 |

1% |

Source: INEGI, 2018.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper, we sought to

explore elderly museum use and access in Mexico using new national level data

in the context of active ageing, with a focus on personal, social, and physical

dimensions. We found that some elders are able to use museums for recreation,

learning, and maintaining social connection and engagement, though their

preferences and obstacles may at times vary from those of younger adults. At

the same time, some findings hint at potential exclusivities that may reduce

the ability to participate in certain groups. We consider future avenues for

research below.

While we did not

measure the average price of entry or senior discount information,[2] we know that having leisure time and disposable

income are signs of relative class advantage, in addition to transportation

options like private vehicles. Other hints that income/wealth matters include

the high proportion of highly educated visitors among elderly and younger

adults, the use of tourist industry services to learn about, travel to and

visit museums, and the ability to visit without planning, as reported by nearly

half of respondents. How income/wealth precisely impacts the interest, access,

and use of museums by elderly visitors in Mexico and elsewhere is a worthwhile

area of continued study.

We are also able

to infer the importance of proximity and transportation access to museum use.

Since 48% of visitors did not plan their visits, and over 50% of visitors in

each age group in both rural and urban locations traveled 30 min or fewer to

reach a museum, it appears that convenience helps to play a role. This finding

should be analyzed in the context of ability differences among elders –

continuing to find ways to enhance design and programming to enable people with

mobility support needs to enjoy museums would likely improve the active ageing

potential of museums. Similarly, women relied more heavily on public transport

matters – in places where transit is sparse, this may affect some women’s

ability to visit. Transportation access will largely be decided by local and

regional planning and policy decisions and, therefore, likely be outside museum

purview. Still, museums might in some cases, be able to partner with public

transit agencies or private transportation companies for specialized services

to improve access.

Findings also

hint at other opportunities to support active ageing through museum

programming. While 44% of museums in the INEGI database reported providing arts

and cultural programming, only 5% of respondents in the same year reported

using such services. Elders in particular, and adults in general, report

cultural engagement as a priority motivation to visit and likely achieve a

degree of cultural satisfaction through exhibits and guided visits. However,

activities outside of exhibits might offer greater opportunities for meeting

new people, considering that most of the social interactions we measured among

elders were based on preexisting social relationships. For folks who visit

alone or individuals who could use an expanded social network, such structured

activities could be helpful. In general, greater qualitative and qualitative

inquiry into the curiosities and interests of existing and potential patrons

could help create museum spaces that invite and retain elderly visits. Lastly,

museums offer institutional mechanisms to support lifelong learning. Whether or

not learning was reported as a motivation, a high proportion of visitors

reported high learning outcomes. To continue to support active ageing,

increasing museums access and use among elders will be critical.

Bibliographic

References

Antón,

C., Camarero, C. & Garrido, M. J. (2018). Exploring the experience value of museum visitors as a

co-creation process. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(12),

1406-1425.

Antón, C., Camarero, C.

& Garrido, M. J. (2019). What to do after visiting a museum? From

post-consumption evaluation to intensification and online content generation. Journal of Travel

Research,

58(6), 1052-1063.

Antunes, M. & Jesús, C.

(2018) O museu como contexto de educação comunitária: um projeto de promoção do

envelhecimento bem sucedido. Estudos Interdisciplinares Sobre o Envelhecimento, 23(1),

9-26.

Attoh, K. (2017). Public transportation and the idiocy of urban

life. Urban Studies, 54(1), 196-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015622759

Camic, P. M. & Chatterjee, H. J. (2013). Museums and

art galleries as partners for public health interventions. Perspectives in

Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913912468523

Cardozo, C., Martín, A. & Saldaño,

V. (2017). Los adultos mayores y las redes sociales: analizando

propuestas para mejorar la interacción. Informe Científico Técnico

UNPA (ICT-UNPA), 9(2), 1-29.

Coffee, K. (2007) Audience research and the museum

experience as social practice. Museum Management and Curatorship, 22(4),

pp. 377-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701757732

Del Chiappa, G., Andreu, L.

& Gallarza, M. G. (2014). Emotions and visitors’

satisfaction at a museum. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and

Hospitality Research.

Dickens, A. P., Richards, S. H., Greaves, C. J., &

Campbell, J. L. (2011). Interventions targeting social isolation in older

people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-647

Elottol, R. & Bahauddin, A.

(2011). Practical Step towards integrating Elderly Pathway Design into Museum

Space planning Framework of Satisfaction Assessment. International

Transaction journal of Engineering, Management and Applied Sciences and

Technologies, 2(3), 265-285.

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Robine,

J. M., Walker, A. & Kalache, A. (2013). Active

ageing: A global goal. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/298012

Fernández-Mayoralas,

G., Rojo-Pérez, F., Martínez-Martín, P., Prieto-Flores, M. E.,

Rodríguez-Blázquez, C., Martín-García, S., Rojo Aubin, Forjaz, A. M. (2015). Active ageing and quality of life: Factors associated

with participation in leisure activities among institutionalized older adults,

with and without dementia. Ageing and Mental Health, 19(11),

1031-1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.996734

Foster, L., & Walker, A. (2013). Gender and active

ageing in Europe. European Journal of Ageing, 10(1),

3-10.

Freixas,

A. (1997) Envejecimiento y género: otras perspectivas necesarias, Anuario de

Psicología, 73, 31-42.

García, N. (Ed.) (1993) El Consumo Cultural en

México. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes.

García,

N. (1999) El consumo cultural: una propuesta teórica. En: Guillermo Sunkel

(Coord.). El Consumo Cultural en América Latina. Colombia: Convenio Andrés Bello.

García, J. (2016) El acceso del adulto mayor al

sistema de transporte público: implicaciones sociales más allá de la movilidad.

In: Concha Mateos

& Javier Herrero (Coords.).

La Pantalla Insomne.

Tenerife: F. Drago.

Galvanese, A. T. C., Coutinho, S.,

Inforsato, E. A. & Lima, E. M. F. de A. (2014). A produção de acesso da população idosa ao território

da cultura: uma experiência de Terapia Ocupacional num museu de arte. Cadernos

de Terapia Ocupacional Da UFSCar, 22(1), 129-135. https://doi.org/10.4322/cto.2014.014

Gilabert

González, L. M. & Lorente Guerrero, X. (2016). Los museos como factor de

integración social del arte en la comunidad. La experiencia del Voluntariado

cultural de mayores. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_cuts.2016.v29.n1.49247

González-Oñate,

C., Fanjul-Peyró, C., & Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, F. (2015). Uso, consumo y

conocimiento de las nuevas tecnologías en personas mayores en Francia, Reino

Unido y España. Comunicar, 23(45), 19-27.

Guerra, E. (2014). The built environment and

Car use in Mexico City: is the relationship changing over time? Journal of

Planning and Education Research, 34(4), 394-408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X14545170

Guerra, E., Caudillo, C., Monkkonen,

P. & Montejano, J. (2018). Urban form, transit

supply, and travel behavior in Latin America: evidence from Mexico’s 100

largest urban areas. Transportation Policy, 69, 98-105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.06.001

Ham,

R. (1999) El envejecimiento en México: de los conceptos a las necesidades. Papeles de Población, 5(19), 7-21.

Harbering, M., & Schlüter, J. (2020). Determinants of

transport mode choice in metropolitan areas the case of the metropolitan area

of the Valley of Mexico. Journal of Transport Geography, 87,

102766.

Hovi‐Assad, P. (2016) The Role of the Museum in an Ageing

Society, Museum International, 68(3-4), 84-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12129

Hsieh, H. J. (2010). Museum lifelong learning of the

ageing people. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2),

4831-4835). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.779

Huenchuan,

S. & Rodríguez-Pinero, L. (2010). Envejecimiento y derechos humanos:

situación y perspectivas de protección. Comisión Económica Para América Latina

y El Caribe (CEPAL), 144.

Huijg, J. M., Van Delden, A. E. Q., Van Der Ouderaa, F. J. G., Westendorp, R. G. J., Slaets, J. P. J. & Lindenberg, J. (2017). Being active, engaged, and healthy: Older persons’

plans and wishes to age successfully. Journals of Gerontology - Series B

Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(2), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw107

Hernández

Lara, O. (2018). Autónomos, autodependientes y libres en movimiento. Personas

mayores como espacio y tiempo en la atención de las agendas académicas y

pública y foco de interés del sector privado. Ponto-e-Vírgula :

Revista de Ciências Sociais,

22, 97. https://doi.org/10.23925/1982-4807.2017i22p97-102

House, J. S., Landis, K. R. & Umberson,

D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865),

540-545. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3399889

INEGI

(2010). Marco Geoestadístico Nacional, Aguascalientes: INEGI.

INEGI

(2015). Encuesta Intercensal 2015, Aguascalientes: INEGI.

INEGI

(2018). Estadística de Museos, Aguascalientes: INEGI.

INEGI

(2019). Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas, Aguascalientes:

INEGI.

International Longevity Center Brazil-ILC. (2015).

Active Ageing: A Policy Framework in Response to the Longevity Revolution. (P.

Faber, Ed.), Special Eurobarometer.

Jung, E. H. & Sundar, S. S.

(2016). Senior citizens on

Facebook: How do they interact and why? Computers in Human Behavior, 61,

27-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.080

Komatsu, M. (2003). Towards the Development of

Grassroots Cultural Activities: Mexican Cultural Policy and the Case of

Community Museums.

Lubben, J. (2017). Addressing Social Isolation as a Potent

Killer! Public Policy & Ageing Report, 27(4), 136-138. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/prx026

Melgar, J., Medina, M. & Aranda, N. (2013) El

adulto mayor como usuario del transporte Público de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua

México. Paper presented at the XVII Congreso Internacional en Ciencias

Administrativas, Universidad del Valle de Atemajac.

Mo, F., Zhou, J., Kosinski, M. & Stillwell, D.

(2018). Usage patterns and social circles on Facebook among elderly people with

diverse personality traits. Educational Gerontology, 44(4),

265-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2018.1459088

Montero

López, P., Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Zamarrón, M. D. & López, S. R.

(2011). Anthropometric, body

composition and health determinants of active ageing: a gender approach. Journal

of biosocial science, 43(5), 597-610.

Muñoz,

F. & Espinosa, J. (2008) Envejecimiento activo y desigualdades de género, Atención

primaria, 40(6), 305-309.

O’Fallon, C. & Sullivan, C. (2003). Understanding

and managing weekend traffic congestion. Paper presented at 26th Australasian

Transport Research Forum (ATRF), Wellington, New Zealand.

Palmer, V. J., Gray, C. M., Fitzsimons, C. F., Mutrie, N., Wyke, S., Deary, I. J., Der, G., Sebastien F.

M. & Skelton, D. A. (2019). What Do Older People Do When Sitting and Why?

Implications for Decreasing Sedentary Behavior. The Gerontologist, 59(4),

686-697. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny020

Partida, V. (2005). Demographic transition, demographic bonus

and ageing in Mexico. Proceedings of the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on

Social and Economic Implications of Changing Population Age Structures,

285-307.

Pregazzi,

C. (2017) El envejecimiento de la población en México: líneas estretégicas para

preparar la ciudad a las nuevas condiciones demográficas. Revista Entorno Académico, 19, pp. 44-48.

Prince, D. R. (1990). Factors influencing museum

visits: An empirical evaluation of audience selection. Museum Management and

Curatorship, 9(2), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/0964-7775(90)90054-B

Ramos Monteagudo, A. M., Yordi García, M., & Miranda Ramos, M. de los Á. (2016).

El

envejecimiento activo: importancia de su promoción para sociedades envejecidas.

Arch. Méd.

Camaguey, 20(3),

330-337.

Retcho, D. E. (2017). Accessibility to Art Museums and

Museum Education Programs for an Elderly Population with Dementia.

Rodríguez,

V., Montes de Oca, Z., Paredes, M. & Garay, S. (2018) Envejecimiento y

derechos humanos en América Latina y el Caribe. Tiempo de Paz,

130, 43-54.

Rogers, M. L. (1998). An exploration of factors

affecting customer satisfaction with selected history museum stores. Texas

Tech University.

Rosas,

A. (2002). Los estudios sobre consumo cultural en México. In Daniel Mato

(Coord.) (Ed.), Estudios y Otras Prácticas Intelectuales Latinoamericanas en

Cultura y Poder , pp. 255-264, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales

(CLACSO) y CEAP, FACES, Universidad Central de Venezuela. http://observatoriocultural.udgvirtual.udg.mx/repositorio/bitstream/handle/123456789/356/RosasM_Estudios_consumoCultural_Mex.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Rosas,

A. (2007). Barreras entre los museos y sus públicos en la Ciudad de México. Culturales,

III(5),79-104. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=694/69430504

Rowe J. W. & Kahn R. L. (1998). Successful ageing. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. (2015). Successful ageing 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the

21st century. Journals of Gerontology - Series B, 70(4), 593-596.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv025

Salas-Cárdenas, S. M. & Sánchez, D. (2014). Envejecimiento

de la población, salud y ambiente urbano en América Latina. Retos del Urbanismo

gerontológico. Contexto. Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura de la

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, VIII(9), 31-49.

Salazar-Barajas,

M. E., Salazar-González, B. C., & Gallegos-Cabriales, E. C. (2017). Middle-Range Theory: Coping and Adaptation with Active

Ageing. Nursing Science Quarterly, 30(4), 330-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318417724459

Sánchez

González, D. & Cortés Topete, M. (2016). Espacios públicos atractivos en el

envejecimiento activo y saludable. El caso del mercado de Terán, Aguascalientes

(México). Revista de Estudios Sociales, 57, 52-67.

Sandahl, J. (2019) The Museum Definition as the Backbone of

ICOM. Museum International, 71(1-2), vi-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13500775.2019.1638019

Sandell, R. (2003). Museums, society, inequality. Museums,

Society, Inequality, pp. 1-268, Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203167380

Schmilchuk,

G. (2000). Venturas y desventuras de los estudios de público. PORTO ARTE: Revista de Artes Visuais, 11(20). https://doi.org/10.22456/2179-8001.27880

Schmilchuk, G. (2012). Públicos de museos, agentes

de consumo y sujetos de experiencia. Alteridades, 22(44), 23-40. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-70172012000200003&lng=es&tlng=es

Serrano,

A., Ortiz, M. & Vidal, R. (2009). La discapacidad en población geriátrica

del Distrito Federal, México, año 2000. Un caso de geografía de la población. Terra.

Nueva Etapa, 25 (38),15-35. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=721/72112047002

Shieldhouse,

R. G. (2011). A jagged path:

Tourism, planning, and development in Mexican World Heritage cities. University

of Florida.

Sinclair, T. J. & Grieve, R. (2017). Facebook as a

source of social connectedness in older adults. Computers in Human Behavior,

66, 363-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.003

Toepoel, V. (2013). Ageing, Leisure, and Social

Connectedness: How could Leisure Help Reduce Social Isolation of Older People? Social

Indicators Research, 113(1), 355-372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0097-6

Tufts, S., & Milne, S. (1999). Museums: A

Supply-Side Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3), 613-631.

Walker, A. (2009). Commentary: The emergence and

application of active ageing in Europe. Journal of Ageing and Social Policy,

21(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420802529986.

Welti-Chanes, C. (2001). Cambios socioeconómicos y

sobrevivencia de la población mayor. Demos,

14, 25-26.

World Health Organization-WHO. (2002). Active ageing:

A policy framework. World Health Organization. World Health Organization.

Yavuz, N., & Welch, E. W. (2010). Addressing fear

of crime in public space: Gender differences in reaction to safety measures in

train transit. Urban studies, 47(12), 2491-2515.

Yu, R. P., Ellison, N. B. & Lampe, C. (2018).

Facebook Use and Its Role in Shaping Access to Social Benefits among Older

Adults. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 62(1),

71-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1402905

Zamorano, C., Alba, M., Capron, G., González, S.,

& Zamorano Villarreal, C. (2012). Ser viejo en una metrópoli

segregada: adultos mayores en la ciudad de México. Nueva Antropología, 25(76),

83-102.

Oscar Gerardo Hernández-Lara

Mexicano. Doctor

por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Es maestro en estudios regionales por el

Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora y licenciado en

planeación territorial por la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

Actualmente se desempeña como profesor de tiempo completo en la

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Políticas de la Universidad Autónoma de Baja

California. Sus áreas

de investigación e interés son: envejecimiento demográfico, migraciones internacionales, estudios

socioterritoriales, estudios rurales. Sus publicaciones recientes

son: Residential Moves Into and Away from Los Angeles Rail Transit

Neighborhoods: Adding Insight to the Gentrification and Displacement Debate y Envejecimiento y rejuvenecimiento en localidades

rurales en México. Apuntes en prospectiva.

Benjamin Toney

American. Doctoral Candidate in Urban Planning and

Development at the University of Southern California. Mexican.

Bachelor’s Degree in Urban and Environmental Policy from Occidental College.

Areas of interest include marginalized populations, urban form and social

structure, racial justice, and progressive housing activism. His recent

publications include: Boarnet,

M. G., Giuliano, G., Painter, G., Kang, S., Lathia,

S., & Toney, B. (2019). Does transportation access affect the ability to

recruit and retain logistics workers? In Empowering the New Mobility Workforce, pp. 189-219,

Elsevier.